The University of Michigan's legendary football coach Bo Schembechler once famously told the Wolverines that "no man is more important than the team."

The speech has become part of UM's lore, played during football games and is embraced by some as a philosophy that transcends sports.

But former UM football player Jon Vaughn believes there was one man who was more important than UM's teams.

He points to Dr. Robert E. Anderson, a man who rose from a small town in the Upper Peninsula to become a renowned sports doctor at the state's most prestigious university. More than a decade after he died in 2008, Anderson is accused of living a secret life filled with transgressions that went mostly unspoken for decades and almost stayed buried with him.

An accusation by a single victim this year inspired 800 others, mostly men, to come forward and unleash allegations of grotesque behavior. Among those accusations are new findings, details and complaints that several accusers say were largely ignored by university officials.

At least six people say they notified one or more university officials of his behavior, including storied names at UM — such as Schembechler and former Athletic Director Don Canham, along with several other coaches and two high-ranking UM administrators.

Eight months later, questions remain as lawyers and UM engage in mediation starting Friday. Central among them: How did UM fail to stop Anderson from hurting so many people, as the university now concedes he did?

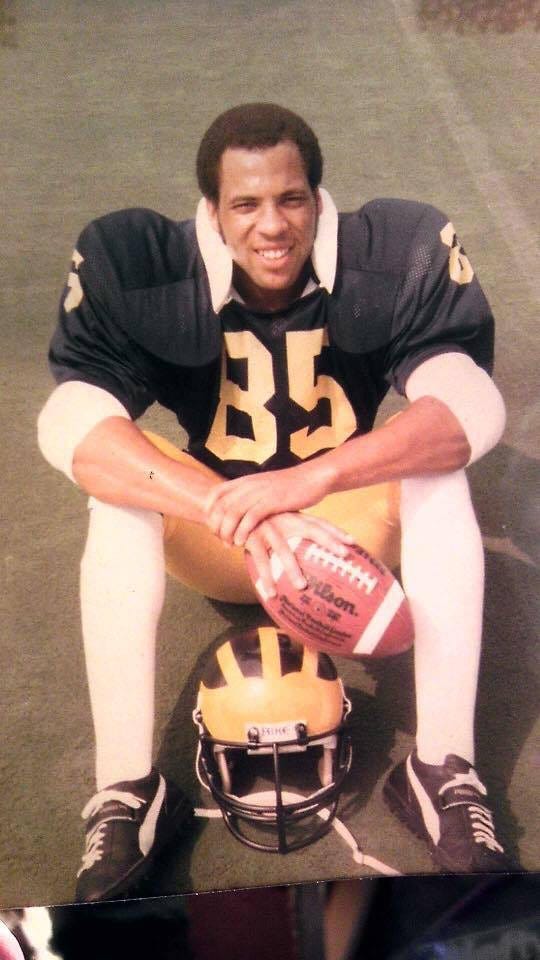

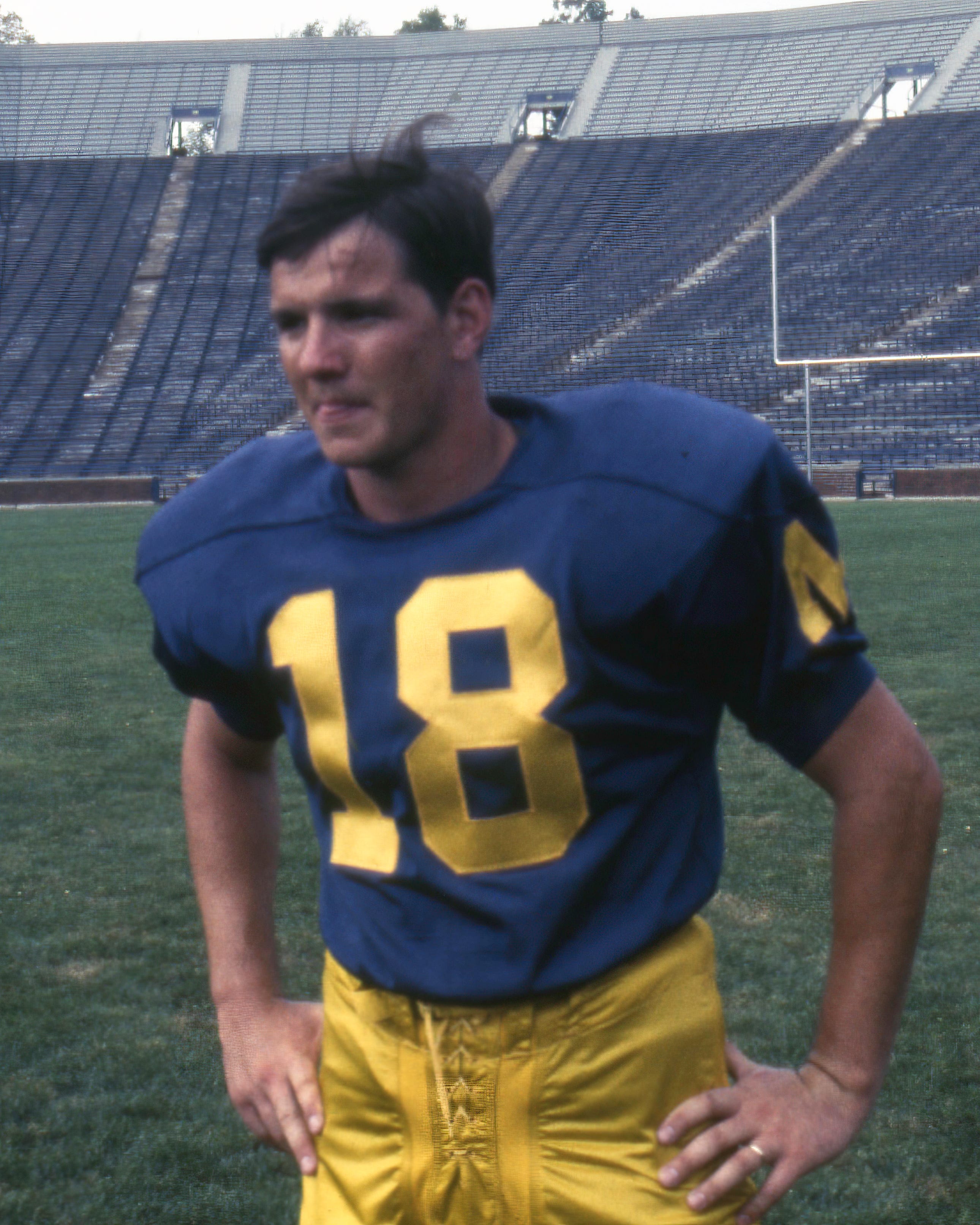

"No man should be greater than the team," said Vaughn, who has sued UM in U.S. District Court in Detroit, alleging he was assaulted by the doctor when he was a running back from 1988-90. "But Anderson was greater than the team because so many coaches, administrators, athletic trainers ... protected this one man. There was an army of enablers that protected this one man. He was above the team."

►Read more: UM's cost from Anderson allegations: $10.7M and rising

According to interviews, police reports and lawsuits, Anderson, as director of the university's health service and team physician for the athletic department over more than three decades, preyed mostly on men, including athletes, along with some women.

His accusers say Anderson gave them prolonged hernia checks, conducted unnecessary prostate exams or engaged in masturbation during exams, earning him the nickname "Dr. Drop Your Drawers Anderson."

Since Anderson's accusers began coming forward in February, The Detroit News has reviewed Anderson's personnel file, a deposition by his former boss and other documents that show UM became aware of the doctor's inappropriate behavior at least twice while he was employed in the university's health service four decades ago.

After an allegation was made to the university in 1979, UM demoted the doctor but allowed him to continue treating students. After a second alleged incident in 1980, UM gave Anderson yet another chance to treat students, transferring him to serve full-time as team physician for the athletic department.

Scores of former male students who played for UM's teams allege Anderson abused them after his transfer, with some claiming he assaulted them on multiple occasions.

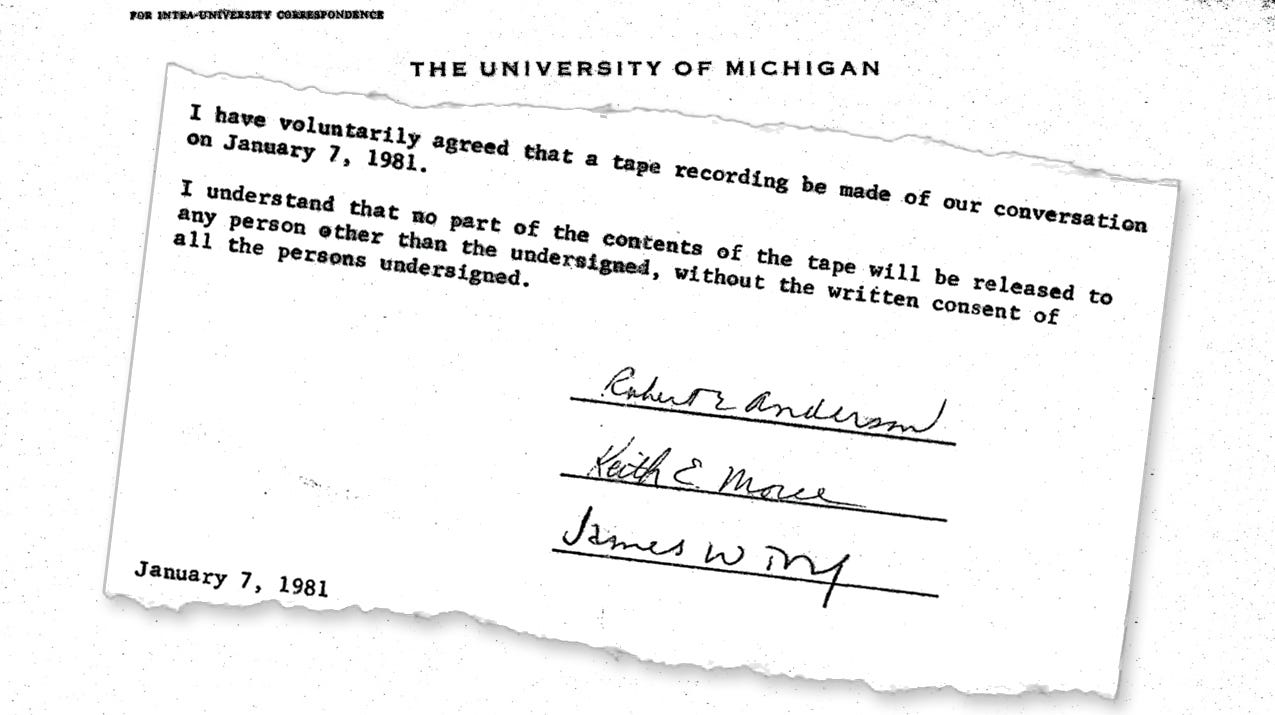

At least one of Anderson's accusers kept evidence against the doctor.

That man, Keith Moree, recently rediscovered a document on UM letterhead, which he had signed almost 40 years earlier as a 20-year-old student, and shared it with The News.

Moree said the document was tied to a meeting he attended after he raised concerns about a May 28, 1980, medical exam with Anderson in which Moree revealed to the doctor that he was gay. Moree said Anderson commented on the fact that Moree was circumcised, discussed the pleasures of masturbation and then appeared to masturbate while Moree's pants were down.

►Timeline: Key events in Anderson's life, career and sex abuse case

Moree says he had filed a formal complaint about Anderson through UM's Office of Student Services after talking with Jim Toy, UM's first on-staff gay male advocate. Moree said Toy told him another student had a similar experience with Anderson and had made a complaint, but it went nowhere.

After filing the complaint, Moree said he also met with Thomas Easthope, then UM's associate vice president for student services, who said he would investigate.

On Jan. 7, 1981, Moree signed the document, which stipulated a meeting that day with Anderson, Easthope and Toy would be recorded, but no contents of that conversation would be released, Moree told The News.

Also signing were Anderson and Toy.

"(Anderson) apologized for what he had done and the effect it had had on me in a very general way," Moree said.

Afterward, Easthope also apologized to Moree, the former student said. Moree said Easthope told him he considered firing Anderson but was concerned about his family if he lost his job.

According to Moree, Easthope made a deal: He said he would move Anderson to an administrative job so he would have no more contact with students. This agreement worked for him and Toy, Moree said, because they didn't care what happened to Anderson. They shook on it, he said.

"We wanted him not to have access to students anymore, not in a medical capacity," said Moree, now 61 and living in Portland, Oregon.

Moree graduated from UM and left the state soon after that meeting. He never followed up on whether Anderson was moved from his position. So he was stunned earlier this year when he learned Anderson had continued treating patients, and that scores of other men subsequently claimed Anderson abused them.

"How could this have gone on for so long to so many people when the university already knew about it?" said Moree, who also outlined his allegations in a lawsuit filed against the university in U.S. District Court in Detroit.

"I did something for the well-being of other people. ... Then to find out that all these other people had these horrible experiences for decades. That was preventable. It never needed to happen, and my university had allowed it to happen on their property in their medical offices with the athletes. I couldn't believe it."

But in a recently unsealed deposition taken July 28 and Aug. 4, Easthope said he didn't remember Moree. The tape and apology were not part of the questions posed to Easthope. But he called the other accusations "pure bulls---."

Allegations of sexual assault came 12 years after Robert E. Anderson died in 2008, revealing a side of the University of Michigan doctor that had almost stayed buried with him. Since then, many others have come forward.

"I never talked to somebody like that," Easthope testified. "Where does he get that from? I read something that he went to my office in the administration building. I don't have an office, I never had an office in the administration building. He might have been talking about somebody else; he wasn't talking about me. ... It pisses me off to have somebody accuse me of something I didn't do."

Easthope did not return messages left on his home phone.

Despite Easthope’s strident denial of Moree's account, within months of the January 1981 meeting, Anderson was moved again, according to the doctor's personnel file, which The News obtained last month through the Freedom of Information Act.

And this time, he was transferred out of the university health service entirely.

►Subscribe for full access to stories, galleries, videos and more

The month after the meeting with Moree, on Feb. 20, an appointment change request was entered into Anderson’s personnel file altering his position to senior physician, athletics, effective July 1.

Four months later, the process still was not complete, unsigned handwritten notes in his file suggest.

“Get second page signed,” reads a note dated June 18, the same day he gave a lecture on athletic training to UM officials and staff. “Dana working on athletics posting.”

And on July 16, more than two weeks after he began his new position, handwritten notes suggest that Anderson would need to be placed on payroll for the minor UM clinical appointments he held “even if other problems are not cleared up.”

UM spokesman Rick Fitzgerald declined to comment when asked about the alleged incident and taped January 1981 meeting between Moree, Anderson and Toy.

"We have nothing to share while the WilmerHale investigation continues," said Fitzgerald, referring to a law firm hired by UM to investigate Anderson and the alleged abuse.

But a newspaper report indicates his move to the athletic department could have been in the works before Moree confronted the doctor at the meeting in January 1981.

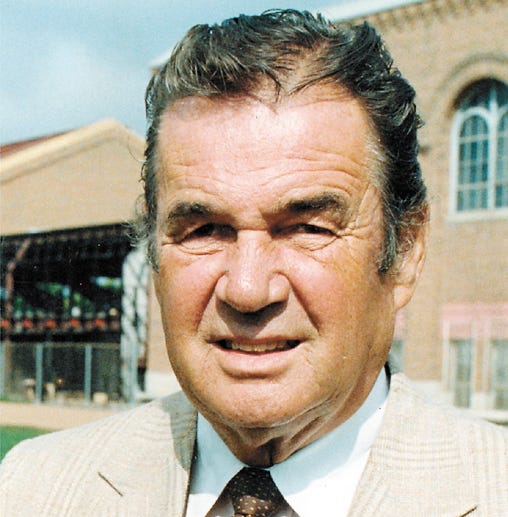

In 1980, Anderson told Canham he intended to leave the student health service to return to private practice, according to a 1999 Ann Arbor News article.

Canham, according to the article, made a pivotal decision: He created a formal position for an athletic team physician and offered it to Anderson, who had been treating athletes on a volunteer basis since the late 1960s. Anderson said he accepted the position immediately.

"Don Canham was a bigger man than Henry Johnson and probably 90 percent of the people up the hill," Easthope testified during his deposition. Johnson was vice president for student services.

During a 2018 UM police investigation of Anderson, the chief detective, Mark West, contacted Russell Miller, who was the athletic trainer during Anderson's tenure at UM. Miller told West that Canham had "worked out a deal" for Anderson to work in athletics, according to a UM police report.

As for Moree's account, Toy told The News he also had a copy of a memo in which Moree described the incident with Anderson, and he remembers meeting with Easthope. But he did not have a copy of the tape of the meeting.

Toy, now 90, said he did not remember many of the details because so much time has elapsed. But he said he also had a troubling experience with Anderson during a rectal exam when he was a UM graduate student.

"I made a noise ... and he is behind me, in a position of power, and almost in a whisper said, 'Jim, I thought you would enjoy it,'" Toy said. "He may have abused many other or some other students."

'A compromising position'

Anderson's behaviors in the exam room didn't become public until a 69-year-old California man came forward this year, alleging Anderson had sexually assaulted him during an exam in 1971.

Robert Julian Stone's account in a Detroit News interview prompted scores of other accusers and two UM police investigations, including one that showed Anderson was almost fired by Easthope in 1979 for his alleged behavior. Instead, Anderson managed to stay at UM until retiring in 2003, five years before his death.

UM now faces roughly 235 lawsuits and so far has spent $10.7 million defending the university, providing counseling services and investigating Anderson, UM's Fitzgerald said. Among the victims are scores of former students who came to UM on athletic scholarships.

Many are African American men. At least one man is dying of advanced prostate cancer because he couldn't bring himself to see a doctor, allegedly due to the trauma he carried because of Anderson's abuse. Hundreds of others intend to sue, lawyers say. In response, UM officials have apologized, set up free counseling and hired the WilmerHale law firm to investigate.

In a recent court filing, lawyers for UM said the university "condemns Anderson's misconduct ... recognizes the harms he caused and is committed to developing a fair, just, timely, and efficient resolution process — one that does not require drawn-out litigation."

But UM also filed to dismiss the cases.

"It was filed decades too late," the university said in its filing. "Anderson has been dead for 12 years; he has not been employed by the University for 17 years; and the conduct at issue ... occurred more than 30 years ago."

Additionally, the statute of limitations had long expired, UM said in its motion.

UM acknowledged in a court filing that Anderson had abused some students and said it was "determined to acknowledge and reckon with that past and, to the extent possible, provide justice — including in the form of monetary relief — to Anderson’s survivors."

Beyond the doctor's alleged abuse, few details have been publicized about who Anderson was, and the path that led him to work at UM starting in the 1960s.

Chuck Christian, a former UM tight end, portrayed Anderson as outwardly professional, always wearing a white physician coat. But Christian said Anderson manipulated him and other patients in vulnerable situations.

"He would find ways to get you in a compromising position," said Christian, 61, who has terminal prostate cancer, which he attributes to a fear of exams that grew from Anderson's alleged abuse.

Christian remembered Anderson's brown hair and how it was matted down to his head. He also remembered the sound of a glove snapping when Anderson asked him to bend over, and his "extremely fat fingers."

He said it's difficult to explain why, but Anderson "was creepy."

"If he weren’t a doctor, then you wouldn’t have let him babysit your kid," Christian said.

But not everyone had the same experience.

Roger Elford, a retired high school principal in Owosso Public Schools, regarded Anderson as his personal physician during the 1960s. His doctor-patient relationship with him began when was a high school athlete in Flint, and it continued when he entered college. He recalled Anderson as a kind man who asked about his education and aspirations.

"I found him to be a very helpful, caring and understanding doctor," Elford said. "He still, even in death, holds a very positive place in my memory."

Elford, 76, was shocked when he heard about allegations against Anderson and didn't initially believe them. But as the accusations piled up, he began to feel conflicted.

"If it's true, it's horrible," he said. "But I don't have anything to base that truth on."

Elford also is struggling with why so many people would come forward decades later.

"Why now?" he said. "What has changed in nearly 50 years to bring those claims now? That part I don't understand."

An accuser goes public

Stone said he came forward for many reasons, including personal closure.

After telling West, the UM police detective, in 2019 that Anderson had once grabbed his hand and used it to fondle the doctor's genitals, Stone learned he was not the only person to accuse the doctor of abuse.

He said he also learned that UM was aware of Anderson's behavior and moved him from the University Health Service to become team physician for the UM Athletic Department.

Stone, now 70, said he hoped his story would lead other potential male victims to speak up amid the #MeToo movement, which has promoted justice for women who have been sexually harassed and abused.

"If men don't start coming forward, these things are just going to go on," he said. "We need to have a dialogue about this and we need to have this dialogue on a national level."

When Stone's story became public in February, UM announced its police department had been investigating allegations against Anderson for 19 months.

Anderson's path to UM

Anderson was born Feb. 20, 1928, in L'Anse, a village in the northwest part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula.

He graduated from L'Anse High School in 1946, district superintendent Susan Tollefson said. A composite photo of his senior class shows Anderson graduated with 53 people and was class president. He also was the valedictorian, according to his published obituary.

Afterward, Anderson enrolled at Michigan State University, where he earned a bachelor of science in zoology in September 1950, MSU spokeswoman Emily Guerrant said.

Anderson then attended UM, where he earned his medical degree in 1953 and did an internship and residency at Flint's Hurley Hospital and University of Michigan Hospital between 1953-57, according to documents in his personnel file.

After his internship, Anderson was in private practice from 1957-66 in Flint. There, he started a program that provided free physical exams to high school athletes, according to the Ann Arbor News.

"At that time, there was not any real designation of sports medicine," Anderson told the newspaper for an article published in June 1999, when he retired as UM’s team physician. "We got together a group of people ... and organized a program for preparticipation physicals and coverage of all Flint high schools."

During those years, Anderson also served as chief of the health service at the General Motors Institute of Technology (now Kettering University) and as director of the health service at Flint Junior College (now Mott Community College), according to his UM personnel file.

As his career progressed, Anderson and his wife, Jacquelyn, began building their family: Eric, born in 1957, Jill, born in 1960, and Kurt, born in 1964, according to public documents.

He moved back to Ann Arbor in 1966, according to his obituary. That is when he became an associate physician at the UM Health Service, earning $16,000 annually.

Two years later, in 1968, Anderson became director of the University Health Service.

Barbara Newell, who was acting vice president for student affairs at the time, recommended Anderson for the position in a letter to the UM Board of Regents. She cited his experience in Flint and his published academic papers on athletic medicine and adolescent help.

"His obvious concern for student problems and his extensive activities outside of the University Health Service to aid the total health program of the university lead me to recommend (him)," Newell wrote.

Anderson simultaneously worked as a training physician for the UM Athletic Department beginning in 1968, according to his personnel file. The doctor also worked in the university's medical school in the Internal Medicine Department.

His research spanned male infertility, problems referable to student health and male gonadal dysfunction, which are disorders of the testes, according to his personnel records.

As Anderson was starting his career, UM was expanding its renowned athletic program under Canham. Anderson spoke with the then-athletic director on a plane ride back from a football game in 1968 and later wrote him a letter, lobbying him to make physicals routine for all athletes to help diagnose problems and lower costs, according to a March story in the Detroit Free Press.

At the time, sports physicals were not mandatory. Canham, who is now deceased, agreed to Anderson's suggestion.

The same year, Canham hired Schembechler as head football coach, starting a two-decade run that lifted the Wolverines to greater prominence and success, including 17 bowl game appearances.

In a lawsuit filed in July against UM in Detroit's U.S. District Court, a former UM student who was an announcer during Wolverine football games alleged he told Schembechler about Anderson after seeing him for migraine headaches in 1982 and 1983.

The man — who spoke during a virtual press conference and did not reveal his identity — said Schembechler's reaction led him to believe it was the first time the coach had heard about Anderson's conduct.

"What Bo said to me when I first came to him was, 'Get your butt into Canham's office and tell him what happened right now,'" the former student said.

He blamed Canham, not Schembechler, for failing to pursue his complaint. He said Canham blew him off when he told him about Anderson, effectively failing to prevent "hundreds, if not thousands, of acts of sexual abuse."

"In my opinion," the man said, "Canham perpetrated Anderson's abuse."

Vaughn, for his part, believes his coach shares the blame.

“The decision of knowing that your players, that you call family, that you go into their homes and speak to their parents at recruiting trips that their child is going to be protected under your watch and you do nothing?" he said. "How can Schembechler not be held accountable for that?"

Schembechler, like Canham, is deceased.

'People loved my dad'

Anderson's children did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

But daughter Jill Anderson, who lives in Ann Arbor, spoke at length with The News in February, days before Stone’s accusation became public.

She said her father was an internist and a specialist in andrology, the study of male hormones. He also practiced sports medicine after becoming interested in it during his graduate training in Flint.

Besides serving at UM, Jill Anderson said her father had a private practice in andrology that included helping men with fertility struggles conceive a child with their partners. He was at the forefront of sports medicine, she added, and established national protocols for screening young men for athletics.

She said her father also started a clinic at UM's University Health Service for students needing care for sexually transmitted diseases and did contract work outside UM, including conducting physicals for the Federal Aviation Administration.

People loved my dad because he was a gentle soul. He was kind and took care of so many athletes over the years. He was a doctor for so many people. ... I can’t imagine my dad would ever have done that. He was a very well respected doctor.

He was highly regarded by his colleagues, his daughter said.

Jill Anderson struggled to reconcile the allegations with the father she knew.

"People loved my dad because he was a gentle soul. He was kind and took care of so many athletes over the years," she said. "He was a doctor for so many people. ... I can’t imagine my dad would ever have done that. He was a very well respected doctor."

Anderson's youngest son, Kurt Anderson, concurred with his sister about his father's character when contacted in mid-February about Stone's allegation.

"When he passed away, it was patient after patient who said they loved him and he was great," said Kurt Anderson, who lives in Florida.

He said he never heard anyone say they experienced the abuse Stone described. "My dad was completely heterosexual," Kurt Anderson said.

The doctor and his wife, also known as Jackie, were married from 1952 until his death, according to his obituary. Jill Anderson said her mother, now 92, has dementia.

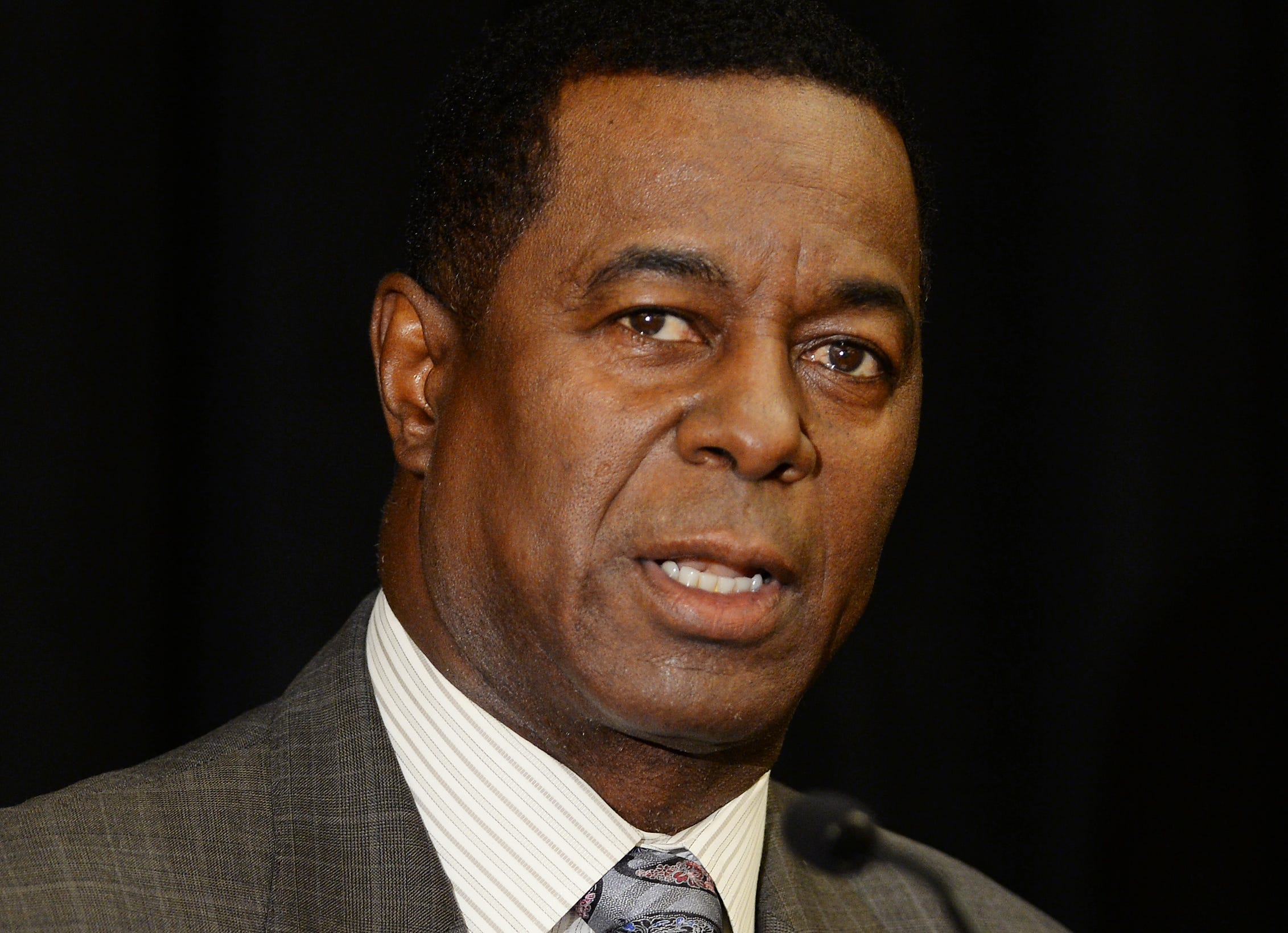

Dwight Hicks — a co-captain of the UM football team in the 1970s and two-time Super Bowl champion with the San Francisco 49ers — said he understands how Anderson's family would want to remember the positive things he did throughout his life.

But Anderson had another side, said Hicks, who came forward as an accuser at a news conference in August.

"Dr. Anderson took advantage of his position, plain and simple," said Hicks, 64. "I feel sorry for the family that has to endure this. But what about the people who had to endure this (abuse) and the emotional scars?

"His family was not in his office when he was examining us. So what's behind closed doors, they don't know. You still have to respect the love they have for their family member."

'Let's continue the studies'

In 1968, sexual misconduct was allegedly occurring in Anderson's office.

John Gabler Sr. went to UM's health service to get a physical so he could play football for the Wolverines. During the exam, he said, Anderson asked him a question: "Would you like to be part of the studies that I am doing?"

Gabler, now 72, said he was naïve and agreed to participate in the studies, which Anderson told him were about male sexuality.

But those studies, Gabler says, involved Anderson asking him to remove his pants every time he saw the doctor, whether he was seeking pain medication or treatment for a cold. Gabler alleges the doctor touched and penetrated him at least 30 times between 1967 and 1970 when he attended UM.

When Gabler told Anderson he had to go to Detroit's Fort Wayne to get a physical for potentially being drafted to serve in the Vietnam War, he says the doctor told him he was involved in those exams and would arrange for him to avoid serving.

"When I got down there, I didn’t even have to take a physical, I was 4F (unfit for duty)," Gabler said. "He said, 'See? I told you what I’d do for you. Now let’s continue the studies.' I don’t know what it was at that time. But now, you look back and say it was a bribe or something."

Around that same time period, in 1968, a former student allegedly reported Anderson's behaviors to UM.

Gary Bailey, a gay man who earned three degrees from UM, said he went to see Anderson, who allegedly asked him to feel the doctor's genitals, Bailey said.

"I realized that even the doctor, being an authority figure, that this had gone too far," said Bailey, who's 73 and lives in Dowagiac in southwest Michigan. "Gay people had to keep a lot of things hidden back then. Maybe he thought he could get away with it."

Bailey didn't speak publicly until after Stone accused Anderson of sexual assault, though he said he reported the incident on a piece of paper at UM's health service after it happened. His complaint, however, went nowhere.

"I never heard anything back and never followed up on it," Bailey said. "After all, he was the head of the health service."

'That's 'Lefty' for you'

In 1979, when the UM cross country team met at the beginning of the school year for sports physicals at the University Health Service, all were examined, one by one, recalled Eric Hagemeister, a member of the squad.

Afterward, team members talked about how the exam took longer than usual when the doctor checked for testicular cancer, Hagemeister said.

One teammate made an off-hand comment.

"He said, 'that’s Lefty for you,'" said Hagemeister, who said he did not experience anything inappropriate with Anderson and believed the nickname to mean the doctor was left-handed. "He used the term ’Lefty.' ... We all felt like it was more thorough than someone checking for testicular cancer."

Dr. Airron Richardson, who attended UM as a pre-med student and wrestled for the university from 1994-98, said Anderson fooled him, too.

"His go-to line was, 'I'm an expert in cancer,'" Richardson said. "He made you feel like he was checking you so you didn't have cancer."

Now a Chicago-area physician, Richardson said young men are not the age group that needs screening for prostate cancer.

"That's what a manipulator does," he said. "You may think what they are doing is weird, but you can buy it."

Anderson's unusual behaviors during exams prompted discussion among his patients, but they were also brought to the attention of the state.

At least two complaints were recorded with the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs against Anderson during the 1980s and 1990s, but they went nowhere. One was opened Feb. 11, 1988, and closed May 4, 1988; another was opened May 13, 1994, and closed March 16, 1995, according to state officials. State officials destroy documents after five years, so additional details were not available.

Numerous other allegations also emerged in lawsuits from John Does, including some who said they reported Anderson to other university officials such as UM head track coach Jack Harvey, and assistant coach Ron Warhurst, in 1976, and UM Assistant Athletic Director Paul W. Schmidt in the 1980s. All have denied they were told about Anderson.

A key moment occurred in 1979 when Anderson was confronted by Easthope, his superior, about his alleged actions.

Easthope told UM police in 2018 that he approached Anderson after reports from a gay advocate that the doctor was assaulting male students during exams.

Easthope told police that though Anderson was a "big shot," he would "never forget walking across the campus to fire" the doctor. Easthope said Anderson just looked at him and did not deny the allegations.

"You gotta go," Easthope is quoted in the police report as telling Anderson. Easthope's wife reminded him during the interview that Anderson was allowed to resign as head of the health service. Two years later in a deposition, Easthope said repeatedly that he fired Anderson.

But Anderson's personnel file shows the university demoted him to senior physician in January 1980, a year before he became team physician in UM's athletic department.

Easthope also testified during his deposition that his boss, Johnson, overturned the decision to terminate Anderson. However, Easthope also acknowledged that he did not alert others about Anderson's behavior, such as police, prosecutors or state licensing officials, or follow up to ensure Anderson was gone.

Johnson has declined comment and has retained a lawyer. He is expected to be deposed before the end of the year, lawyers said.

Harold Shapiro — who served as UM's president from 1980-87 and later as Princeton University president — said he remembered Easthope and Johnson. But Anderson's behavior was never brought to his attention, he said.

Asked if he would have acted, Shapiro, now a Princeton faculty member, said it's all speculation.

"I would hope I would have," Shapiro said.

A retirement, then a reckoning

Anderson, known by some as "Dr. A," was celebrated when he retired in 2003, with many hailing his service to UM.

Five years later, in the early morning hours of Nov. 27, 2008, Anderson died in his Ann Arbor home on Seventh Street of pulmonary fibrosis, a lung disease, according to his death certificate. He was 80.

Well-wishers offered personal and professional accolades, according to posts on legacy.com.

Among them was Henry Johnson of Ann Arbor. He wrote he would "remember Bob as a highly competent physician, administrator and friend."

"He was always there for me. His contributions to the high quality of health care for students are well documented," wrote Johnson, adding he would be unable to attend the services due to a longstanding out-of-town commitment. "I will remember him always as a servant leader."

Doug Bentley of Saline recalled Anderson's kindness. "It's humbling to consider the body of work he left behind, but reassuring to imagine this good and great man being welcomed by the Almighty with a resounding 'Well done, Dr. A.,'" Bentley wrote.

Years before Anderson's retirement, Tad DeLuca, a former UM wrestler, had written a letter in 1975 to then-coach Bill Johannesen about Anderson's behavior. But it went nowhere, he said. Johannesen has denied being aware of any abuse by Anderson.

Then on July 18, 2018, DeLuca wrote another letter to UM about Anderson, 43 years after his first.

By that time, the Larry Nassar sex abuse scandal had engulfed Michigan State and powerful entertainment figures such as Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein were facing sex assault charges as the height of the #MeToo movement. Ohio State University also was investigating scores of allegations from former male students who said the late Dr. Richard Strauss had sexually abused them.

The same day that DeLuca dated his letter to UM Athletic Director Warde Manuel, dozens of women made a dramatic entrance onto a stage in Los Angeles to accept the Arthur Ashe Courage Award for speaking out about Nassar's sexual abuse. Sarah Klein was among those who spoke, saying that telling their stories over and over again was not easy.

"We're sacrificing privacy. We are being judged and scrutinized," Klein said. "But it is time. If we can just give one person the courage to use their voice, this is worth it."

It was DeLuca who found his voice again.

In his letter to Manuel, DeLuca wrote that a National Public Radio report about the women who took down Nassar inspired him to come forward and said that Anderson "felt my penis, and testicles, and inserted his finger into my rectum too many times for it to have been considered diagnostic ... or therapeutic ... for the conditions and injuries that I had."

"I am fully aware that it was the 1970s, and it was an entirely different world then," DeLuca wrote. "I am also aware that 40 plus years is an extremely long time ago. I expect nothing. I want nothing. I just feel the need to report this."

Manuel forwarded DeLuca's letter to the university’s office of general counsel. From there, it went to UM's Office of Institutional Equity, which investigates sexual misconduct complaints. But DeLuca's letter languished for weeks before he heard from Pamela Heatlie, the office’s senior director.

DeLuca, now 65, happened to be in the Ann Arbor area, so he spoke with Heatlie on Aug. 27, 2018. He said she asked questions that led him to feel that she believed him. But when he asked if there were other complaints about Anderson, Heatlie said no.

"Oh my God," DeLuca said he remembers thinking. "Am I making this stuff up?"

But soon the chorus of complaints would grow, as former Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox would file the first lawsuit in March against UM then dozens more on behalf of wrestlers, football, track and hockey players. Other lawyers have joined him. Although Cox is a UM graduate, he is critical of his alma mater.

UM knew Anderson was assaulting students and considered firing him twice early in his career — but the university let him stay on for another 24 years and abuse many others, including many young men from low-income families who attended UM on athletic scholarships, Cox said.

Then, UM had an investigation underway that showed more than a year ago that there were numerous alleged victims of Anderson. Stone's decision to share his story with The News forced UM to reveal Anderson's behavior.

"They were two cover-ups at UM," Cox said. "Without Stone, none of this would have happened. Without him, Detective West and you, this would still be buried," the attorney told The News in an interview.

For alleged victims, what happens in the future is more personal.

Vaughn, who went on to play professional football as a running back for the Seattle Seahawks, New England Patriots and Kansas City Chiefs, hopes for fundamental change at the university so this never happens again.

He said it's difficult to cope with the realization at age 50 that he is a victim of sexual assault.

Vaughn said he has not been able to sleep more than a few hours a night since going public. When he does, he has dreams where he can smell Anderson's cologne and feel the doctor's breath on him.

He said he has endured threats from others who don't want UM's reputation ruined, or Schembechler's statue torn down on campus, as Joe Paterno's was after the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal at Penn State University.

But one of his biggest frustrations is "with the university I love, and the actions that have been taken" regarding Anderson's abuse.

"This man was able to do this for 4/5ths of my life and get away with it and retire and go off into the sunset," Vaughn said. "Do you know how many lives have been ruined?"

kkozlowski@detroitnews.com