No nursing homes were the subjects of more complaints from April 1, 2020, through May 31, 2020, in Michigan than the Rivergate complex in Riverview (pictures above) and The Villa at Parkridge in Ypsilanti, according to state records. Andy Morrison, The Detroit News

No nursing homes were the subjects of more complaints from April 1, 2020, through May 31, 2020, in Michigan than the Rivergate complex in Riverview (pictures above) and The Villa at Parkridge in Ypsilanti, according to state records. Andy Morrison, The Detroit News

Riverview — Michigan nursing homes repeatedly failed early in the pandemic to isolate patients with COVID-19, provide minimum levels of care and disclose infections when they occurred, according to documents obtained by The Detroit News and made public for the first time.

More than 1,200 pages of complaints about 67 nursing homes submitted to state regulators in April and May 2020 revealed how the facilities' stumbles allowed COVID-19 to spread, potentially causing more cases and costing more lives.

The records — 167 COVID-19 and staffing-related complaints included in more than 200 overall complaints released by the federal government nearly three years after The News first requested them — point to a litany of concerns about nursing home conditions inside dozens of facilities across Michigan. One nurse in Ludington reported working with a 101-degree fever because there was no one to fill her spot. Another employee at a nursing center in Detroit said patients with COVID-19 had been "left to themselves." Others said facilities with ongoing outbreaks were bringing in new patients despite the danger.

According to the documents, the problems largely occurred amid a shortage of personal protective equipment for staff at nursing homes and sometimes hospitals, as well as a short supply of COVID-19 tests.

The documents raise further questions about staffing levels and orders imposed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's administration at the height of the pandemic. The policies became one of the most debated aspects of the Democratic governor's COVID-19 response, with Republicans contending more residents with the virus should have been cared for in entirely separate facilities to stem the spread. Members of Whitmer's administration said that idea wasn't feasible.

Previously, little has been known about what happened inside the buildings when COVID-19 infections were initially claiming residents' lives.

Whitmer's emergency directives relied on nursing homes themselves to safeguard patients with the virus, provide personal protective equipment for their employees and track cases within their buildings.

Drawing controversy, the orders established a system for treating elderly individuals with COVID-19 in existing nursing homes, requiring residents with the virus to be cared for in dedicated units of their current facilities or transferred to others with proper space and equipment. The administration used the strategy despite a nursing home lobbyist suggesting in March 2020 state officials use empty facilities as quarantine centers to "avoid widespread infection."

In October 2020, the governor and lawmakers provided protections for the nursing homes to limit families' ability to sue them if their missteps led to someone's death.

The legal immunity law came despite the state's Bureau of Community and Health Systems receiving the 167 complaints about nursing homes' handling of COVID-19 or staffing from April 6, 2020, through May 31, 2020, amounting to three complaints each day. One of them was filed by William Woods, 55, of Taylor, whose mother, Johnnie Woods, died inside the Rivergate Terrace nursing home in Riverview on April 19, 2020.

"This is the hardest thing ever that I'm going through," said William Woods, sitting on the couch in his living room with tears in his eyes. "Because in my heart, my mom is not at peace because her killers are still out there, doing the same thing, not getting charged, not being found guilty of what they did.

"If they had the staff members there, my mom would have lived."

Johnnie Woods was 79 when she died April 19, 2020, of respiratory failure, without having tested positive for the virus, William Woods said. That's despite the fact her roommate had COVID-19 and was eventually hospitalized, he said.

Her son argues that a lack of staffing and medical assistance contributed to her body's failure and others' deaths. William Woods said he was inside Rivergate Terrace in April 2020 to stay with his mom during her final days and said he saw residents struggling to feed themselves with no employees around to help them.

Following his mother's death, Woods donned a mask and protested Rivergate Terrace's care of his mother outside of the nursing home along Pennsylvania Road in Riverview near Fort Street.

In a statement, Sujata Chaddha, executive director of Rivergate Terrace, said the facility had faced "unprecedented industry challenges." But Chaddha declined to discuss specific complaints, citing privacy protections.

Melissa Samuel, president and CEO of the Health Care Association of Michigan, which represents nursing homes in Lansing, said facilities did "all they could with the resources and knowledge available at the time to provide the best care for their residents."

"Health care workers and many others stepped up and risked their lives to care for COVID patients," Samuel said. "As the world sheltered in place, dedicated, exhausted, frightened health care staff kept showing up, hour after hour, day after day to care for those in need. Health care workers and thousands of others saved countless lives during this unprecedented, unimaginable time."

'It is a disaster here'

The complaints sent to the state during the first wave of coronavirus infections provide a first-hand account of how dire the public health threat was inside many facilities housing older Michiganians who were already medically frail.

On April 23, 2020 — 44 days after Michigan reported its first cases of COVID-19 — an employee of the Villa at Silverbell Estates in Orion Township submitted a complaint about the facility. Workers there hadn't been trained in how to deal with the virus, and there had been "many deaths here in a short time," the employee told state officials.

"I am a staff (member) working at the Villa at Silverbell, and it is a disaster here," the message began.

The released complaint didn't identify the worker by name, but state inspectors later found the Orion Township nursing home "failed to accurately screen, identify and consistently monitor" residents who had COVID-19 symptoms, according to a June 2020 report.

The failure of the facility, which had 72 residents, "resulted in serious health complications from COVID-19, including the risk of death, for many of whom were at high risk due to age and co-morbidities," the investigative report from state officials said. Officials from the facility didn't respond to requests from The News for comment.

The Villa at Silverbell complaint came eight days after Whitmer released an executive order on April 15, 2020, attempting to set standards for nursing homes' handling of COVID-19 and establishing a "regional hub" system for caring for those with the virus in existing nursing homes. At the time, Dr. Joneigh Khaldun, Michigan's then-chief medical executive, vowed the order would "help ensure that our long-term care facilities are using best practices to keep their residents and employees safe."

By April 15, 2020, the state had already received 34 complaints about nursing homes' handling of COVID-19, including their ability to isolate patients and provide personal protective equipment.

More than 100 complaints came in the weeks that followed the order.

'Would rather die of COVID'

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services has tallied 138,114 COVID-19 cases among long-term care facility residents or staff and 7,430 deaths.

The deaths linked to COVID-19 in the facilities represented about 19% of the statewide total, according to the health department's statistics. But state auditors have questioned whether Michigan's reporting captured all of the COVID-19 fatalities in long-term care facilities, and there were other deaths that occurred amid emergency restrictions that weren't formally linked to the virus.

In complaints filed with the state, family members repeatedly said testing wasn't available for their relatives, raising questions about how well COVID-19 cases were tracked in the early days of the pandemic. On April 10, 2020, a person told officials their mother, a resident of Rivergate Terrace, had a fever and a cough, but there was no test for her.

"I'm very concerned over my mother's health. I haven't seen her in a month, and now, she's put into isolation with symptoms," said the person, whose name wasn't released. "And there's absolutely nothing I can do.

"I want her tested, and I want her tested now."

The early months of the pandemic were a tragic and harrowing time in Michigan's more than 400 nursing homes, said Alison Hirschel, director of the Michigan Elder Justice Initiative, an organization that advocates on behalf of residents of long-term care facilities.

Before the coronavirus arrived, nursing homes struggled to control infections within their buildings, Hirschel said. The facilities simply weren't prepared to respond appropriately to COVID-19 despite state officials making their best effort, she said.

Many of those who lived in nursing homes were locked away in their rooms. Relatives who often helped them get by couldn't visit, and severe staffing shortages made the problems worse, as workers walked away from the low-wage positions, Hirschel said.

"A lot of the residents told us that they would rather die of COVID than live in the isolation that was forced upon them," Hirschel said.

The Whitmer administration's policies widely prohibited visitors to nursing homes for nearly a year from the beginning of the pandemic until March 2021, when the measures were eased after case rates began dropping.

Attorney General Dana Nessel, a fellow Democrat, declined to investigate Whitmer's nursing home policies in May 2021.

The Pandemic Health Care Immunity Act, which was signed by Whitmer on Oct. 28, 2020, retroactively provided civil legal immunity protections for health care facilities and made it more difficult to bring lawsuits against nursing homes, said Donna MacKenzie, a Michigan lawyer who specializes in nursing home abuse cases.

"I think that the governor’s office has responsibility for this immunity and this free pass that (nursing homes) were given to not be held accountable if they didn’t follow the rules that they were being asked to follow," MacKenzie said.

Robert Leddy, a spokesman for Whitmer, said in a statement that Michigan made protecting the health and safety of seniors and most vulnerable residents "a top priority."

"The state of Michigan worked hand-in-hand with medical systems, long-term care facilities and health organizations to put into place best practices that followed CDC guidance," Leddy said. "These policies were eventually passed into law by the Republican-controlled Legislature to ensure that facilities caring for elderly or vulnerable Michiganders were keeping residents safe.

"We know the vast majority of medical professionals followed these guidelines to reduce the spread of COVID-19, and the state of Michigan investigated and worked with facilities that were experiencing issues to help them better protect residents."

3 complaints a day

On June 28, 2020, The News first requested all complaints filed with the state's Bureau of Community and Health Systems from March 1, 2020, through May 31, 2020, against nursing homes or long-term care facilities. The period covered the first three months of the pandemic in Michigan.

The bureau, which is part of the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA), licenses and inspects nursing homes.

Because the complaint process was effectively a joint operation between LARA and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service, both levels of government said they had to sign off on the release of the documents. The arrangement delayed the release of the records for years.

After two years and eight months, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service released the documents to The News on March 13.

Of the 167 complaints against the 67 facilities, at least some aspects of the allegations were substantiated by investigators in 80, or 48%, of the complaints, according to the records. In the other 87, there was either a lack of evidence to support the claims, or it wasn't clear in the documents what investigators ultimately determined.

One employee of Medilodge of Ludington reported on May 4, 2020, that she served residents while having a fever of 101 degrees and chills because there was no one to substitute for her. At the Villages of Lapeer, an employee said on April 7, 2020, he or she had been made to work with fevers and personal protective equipment wasn't made available until there were 13 cases of COVID-19.

On April 24, 2020 — 45 days after Michigan reported its first COVID-19 cases — an employee at Westwood Nursing Center in Detroit, complained the facility was "so short staffed that the patients are just left to themselves." Only about half of the employees at the nursing home on Schaefer Highway were wearing personal protective equipment, the worker said. Meanwhile, the facility continued "bringing in COVID-19 patients," the worker said.

Westwood Nursing Center was located in Detroit, one of the early hot spots nationally for COVID-19. Michigan was hit harder in the first months of the pandemic than most other states when personal protective equipment and tests were scarce.

"Everything is a mess here," the Westwood Nursing Center employee's complaint said.

Investigators later substantiated some of the employee's allegations, finding the facility had deficiencies in its infection control practices.

Westwood didn't respond for comment.

'Dying every shift'

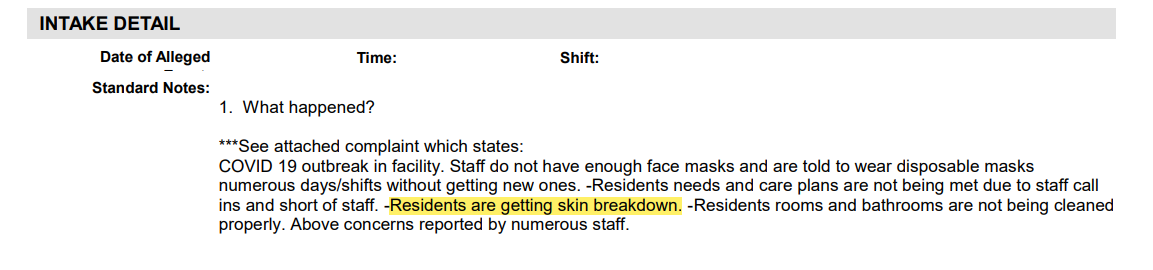

No nursing homes were the subject of more complaints from April 1, 2020, through May 31, 2020, in Michigan than the Rivergate complex in Riverview and the Villa at Parkridge in Ypsilanti. People filed 15 complaints involving COVID-19 or staffing against each facility in that time frame, according to a review by The News.

Investigators substantiated at least some aspects of 10 of the 15 complaints against the Villa at Parkridge, about two-thirds. Officials at the Ypsilanti facility didn't respond for comment.

Meanwhile, investigators substantiated at least some aspects of eight of the 15 complaints, more than half, against Rivergate Terrace and the adjacent Rivergate Health Care Center along Pennsylvania Road.

Tennessee-based Life Care Centers of America runs more than 200 facilities across the country, including the Rivergate complex, according to its website, and is one of the largest privately held nursing home companies in the United States. In 2020, Life Care Centers had $3 billion in revenue, according to Forbes.

Health care workers, relatives of Rivergate residents and the local fire chief repeatedly lodged formal complaints against the Rivergate facility in the spring of 2020 for failing to properly identify and combat a spike in COVID-19 infections. A self-identified registered nurse estimated that close to 100 patients had the coronavirus at 168-resident Rivergate Terrace and seven workers had been sent to the hospital, according to an April 9, 2020, complaint.

The facility had no personal protective equipment as of March 20, 2020, didn't have an isolated area for those with infections and was asking employees to sign "do not disclose papers," the complaint alleged.

"I am reporting it because it is shameful and wrong to ... watch people die because of lack of supplies or proper PPE or greed or proper clean technique(s) or whatever the hell went wrong and continues to go wrong there, but it needs to end," the nurse said. "People are literally dying there every shift."

On April 9, 2020, another individual who identified as an "associate" at Rivergate Health Care Center said seven to eight residents had died with COVID-19 symptoms within a four-day span. Meanwhile, 11 employees had tested positive, the person told state officials.

"The management keeps claiming that we don't have positive cases, but they also haven't tested them either," the associate said.

Likewise, Donna Philip, whose 94-year-old mother, Ruthanne Philip, was rehabilitating inside Rivergate Terrace in April 2020, said she was repeatedly told there were no COVID-19 cases in the facility. Then in early April, Donna Philip personally saw investigators enter the building in hazmat suits.

“I knew COVID was there," Philip said in an interview. "I knew they were lying to me.”

Her mother was hospitalized with pneumonia on about April 20, 2020. After she arrived at the hospital, staff informed Donna Philip her mom tested positive for COVID-19.

Ruthanne Philip died nine days later on April 29, 2020.

A fire chief intervenes

In another complaint on April 9, 2020, Ron Lammers, the fire chief in Riverview, said even his agency was hearing there wasn't proper personal protective equipment at Rivergate and that those with COVID-19 in the facility weren't being quarantined.

"Several of our firefighters have also raised concerns regarding conditions at the facility and many of the above issues," Lammers said in his complaint. "Our run volume has increased drastically over the past couple weeks as well."

Of 29 recent runs, 21 were to Rivergate Terrace, and most were COVID-related symptoms, Lammers reported to state investigators. The facility, experiencing an outbreak, was also calling for non-emergency situations to have patients transferred out of the building, the fire chief said.

"I am told this is an effort to make room for new patients coming from a local hospital," his complaint said.

A day after the complaint, on April 10, 2020, state investigators called for Rivergate Health Care Center to take immediate action to correct and educate its employees on COVID-19 outbreak policies. The report from investigators was dated April 15, 2020, the same day Whitmer signed an executive order on long-term care facilities.

For the entirety of the pandemic, Rivergate Terrace and Rivergate Health Care Center, which operated next to each other, combined to report 892 COVID-19 cases among residents and staff and 80 deaths.

The facility had to overcome "unthinkable challenges," said Rivergate Terrace's Chaddha, who declined to discuss specific cases for privacy reasons.

"Our No. 1 priority has always been the well-being of our patients and staff, and we will continue to focus on that mission," Chaddha said. "We are proud of the heroic efforts our associates have made during the past three years."

Climbed out a window

About 27 miles west of Riverview, family members were repeatedly raising red flags about the care being provided to their relatives at the Villa at Parkridge in Ypsilanti. An unidentified resident of the facility told state officials in May 2020 that she had tested positive for COVID-19 but wasn't being cared for.

"... (She) wanted to leave so she climbed out the window and fell down one story," the complaint said.

State investigators deemed those allegations of sub-quality care and patient neglect unsubstantiated. But they verified similar complaints from others about the Villa at Parkridge around the same time.

Another resident of the facility complained on April 24, 2020, the facility was so short-staffed that she wasn't getting cleaned regularly and had been left lying in her own feces. That same day, a person who identified herself as the wife of a resident said her spouse had to wait over an hour when he requested help.

In both complaints, state investigators substantiated allegations there were deficiencies in the facility's quality of care. In a separate complaint on April 18, 2020, a woman said her mother, a resident of the Villa at Parkridge, had been quarantined with a fever.

But family members hadn't been able to contact her from March 30, 2020, until a nurse called on April 8, 2020, to say the woman was being sent to the hospital because she was having trouble breathing.

The mother tested positive for COVID-19 in the hospital's intensive care unit, where doctors found a severe and infected bed sore with "bone exposure." She died April 16, 2020.

Her daughter said in her complaint to state officials that the bed sore infection and COVID-19 contributed to her mother's "demise."

"I believe that once my mom started with the fever and (they) quarantined her to her room with two other residents that the staff didn't care for her properly with moving her position and cleaning her and toileting her when she needed to use the bathroom," the daughter told state officials, according to her complaint.

Investigators substantiated the complaint's allegation of resident neglect. Overall, during the pandemic, the Villa at Parkridge reported 261 COVID-19 cases among residents or staff and 32 deaths.

In May 2020, state investigators said the Villa at Parkridge had "failed to properly clean and disinfect resident rooms placing all 108 residents and staff at risk for contracting COVID-19."

Problems with reporting

From early in the pandemic, Whitmer's administration heavily relied on nursing homes themselves to report how many COVID-19 cases occurred within their buildings and to track the virus's spread.

The governor's April 15, 2020, executive order for long-term care facilities required them to inform employees of the presence of a resident with COVID-19 "no later than 12 hours after identification" and report all presumed positive cases to the state health department.

In June 2021, as Republican legislators voiced concerns that Michigan's tracking on COVID-19 cases in nursing homes was inaccurate, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Director Elizabeth Hertel told lawmakers the state's numbers were based on tallies that were "self-reported from the nursing homes."

"I don't think that the nursing homes have any reason or incentive to try to hide the deaths that have occurred in their residents," Hertel said at the time.

But the Bureau of Community and Health Systems received dozens of complaints from April 1, 2020, through May 31, 2020, that raised concerns about nursing homes' willingness to be transparent about COVID-19 infections.

Of the 167 complaints from April 6, 2020, through May 31, 2020, 48 complaints, or 29%, focused on nursing homes either allegedly declining to inform employees, families or the public about cases or being unwilling or unable to test patients for the virus.

At the time, Whitmer's administration was touting the need to expand testing in Michigan to identify and isolate those with infections.

On May 5, 2020, a Michigan man's father was rushed from Medilodge of Kalamazoo to the hospital, according to one complaint from the son's wife. The father was found to have "bed sores throughout his whole bottom area" and tested positive for COVID-19, the complaint said.

Medilodge of Kalamazoo didn't contact the family about hospitalization, the complaint said. The hospital had to bathe the patient four times and shave his beard because of his "uncleanliness," the complaint reads.

Investigators substantiated the facility was deficient in its handling of the person's records.

During the pandemic, Medilodge of Kalamazoo reported 162 cases among residents or staff and 22 deaths. Officials of the facility didn't respond for comment.

cmauger@detroitnews.com