Born at The News: WWJ radio celebrates 100 years since launch as nation's first commercial broadcaster

Michael H. Hodges

Michael H. Hodges

For a behemoth that now dominates the local AM radio dial, its beginnings were surprisingly humble.

One hundred years ago Thursday, WWJ radio — Detroit's very first station — was born when Detroit News publisher and radio enthusiast William E. Scripps had a 200-watt transmitter set up in a corner of the sports department. (Today? It's 50,000 watts.) WWJ will air a special show, "WWJ at 100, a Century of News," at 7 p.m. Thursday to celebrate.

WWJ wasn't just first in Detroit. Depending on how you slice things, it was the first commercial broadcaster in the U.S., though when it went on the air that Aug. 20 a century back, it was probably picked up by only a few dozen households in possession of what was, at the time, shockingly high-tech radio equipment.

Asked where he'd locate WWJ in American broadcasting history, Specs Howard, founder of the School of Media Arts in Southfield that bears his name, said without hesitation, "Oh, right near the top."

One-time WRIF program director Fred Jacobs, now head of Jacobs Media Strategies in Bingham Farms, agreed, saying, "It's really been a remarkable run, especially in a world where brands come and go."

Despite WWJ's launch on Aug. 20, regular broadcasting didn't begin until Aug. 31, 1920, when The Detroit News announced on its front page that the "Detroit News Radiophone" service would be on the air every evening, except Sundays. Programming that first night included regularly updated primary election returns, and a recording of singer Lois Johnson.

(While The News founded WWJ, it no longer owns it. After Gannett bought the newspaper in 1986, it had to sell the station to comply with an FCC ruling that a single company could no longer own a newspaper and broadcast outlet in the same market.)

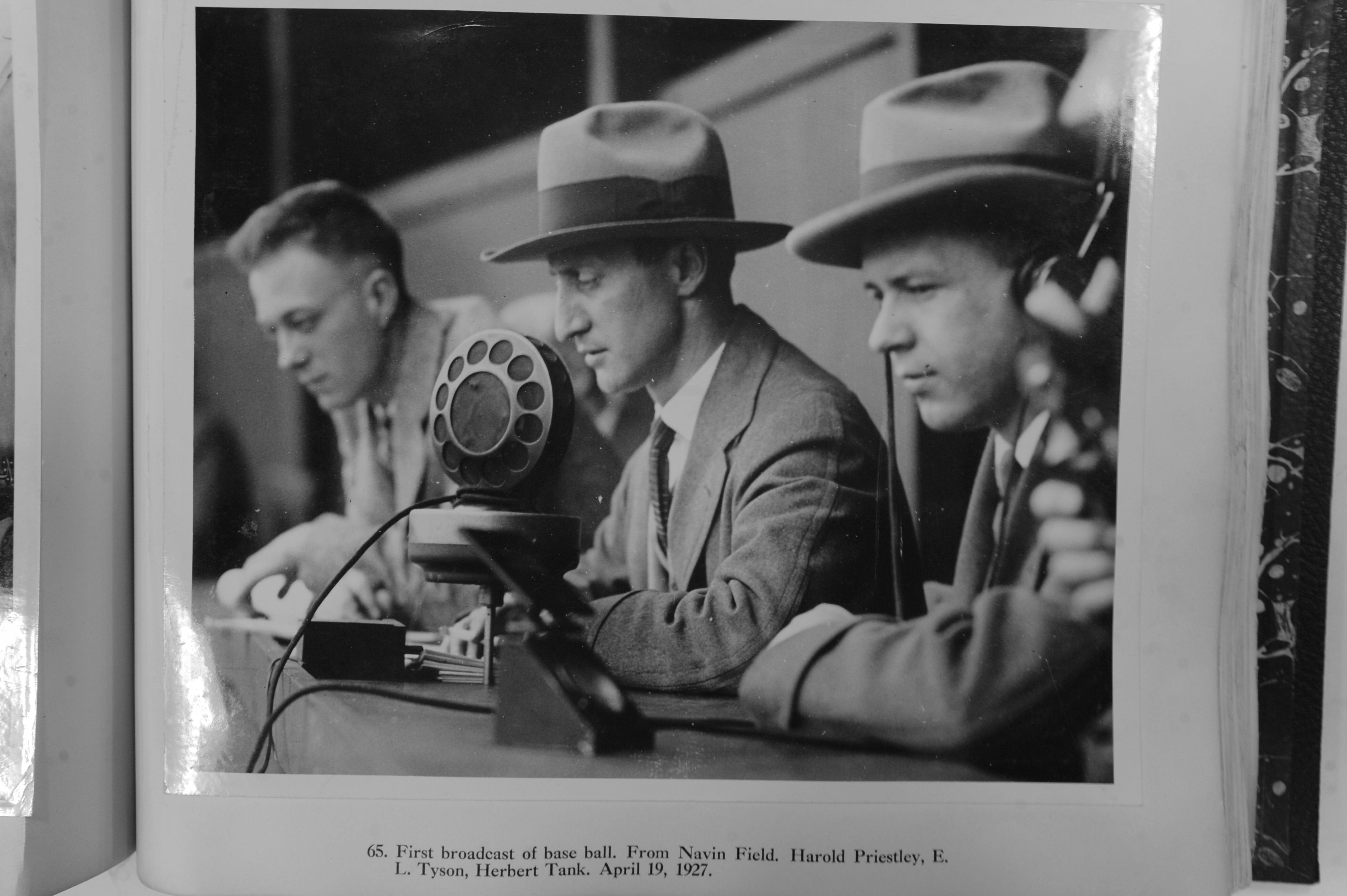

Over the next century, WWJ racked up other nationwide firsts, including the first live concert (with vocalist Mable Norton Ayers, 1920) and the first broadcast of a church service (1922). In 1923, the station aired the first play-by-play coverage of a University of Michigan football game, with celebrated announcer E.L. "Ty" Tyson.

WWJ also helped propel any number of storied careers. Comedian and actor Will Rogers had his radio debut on WWJ, and when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, it was Hugh Downs — decades later, the legendary host of NBC-TV's popular "Today" show — who was at the microphone, trying to make sense of cataclysmic events.

The tradition of larger-than-life personalities continued well into the modern era, from Bob Allison and his call-in show, "Ask Your Neighbor," to Sonny Eliot's antic weather reports.

Allison died this March, Eliot in 2012. Both men left indelible marks.

Roberta Jasina, the reassuring voice of Detroit's morning rush hour, started at WWJ as an intern in 1975, and recalls Allison vividly.

"Bob Allison was a standout," Jasina said. "When I was an intern, one of my jobs was to answer the phone for 'Ask Your Neighbor.' These women loved Bob, and would call to talk about recipes, problems and solutions to household problems. I'm screening those calls thinking, 'Oh my God.'"

She laughed. "It reminded me of that Peggy Lee song, 'Is That All There Is?'"

For his part, auto-beat reporter Jeff Gilbert landed at WWJ in 1990, and was struck by Sonny Eliot's outsized charisma.

"Everybody loved Sonny," he said. "He could get away with so much nobody else could. He’d flirt with every woman who came into station, and they'd all go, 'Oh, he’s so cute!'"

When Gilbert covered auto shows, Eliot would sometimes accompany him — and invariably attract large crowds.

But at one show the weatherman, who was a P.O.W. in World War II, disappeared for a bit. On his return Eliot said to Gilbert, "I just told a Mercedes executive in perfect German, 'I was a guest of your government during the war!'"

Gilbert also reports that Eliot, who did two weather forecasts a day, was forever lugging around a briefcase stuffed with yellowed papers.

"Those were the jokes he’d collected over the decades," he said. "And I mean, they were yellow — like paper that sat somewhere for 40 years."

But long before Eliot appeared on the scene, the station that's become a Detroit institution with "traffic and weather on the 8's" went through a series of name changes before settling on WWJ for good.

Operating on an amateur license in 1920, it was first known as 8MK. When it got its first federal license the next year, the government changed that to WBL.

But the station found people had a hard time understanding those call letters, what with on-air static, so it appealed to federal authorities and was re-christened WWJ in March, 1922.

If only 30 households around Detroit picked up the station's first broadcast in August 1920, by November that had grown to about 500 local residents equipped with receivers. From there on, things went viral.

Today, according to Nielsen, 272 million Americans over the age of 6 tune into the radio at least once a week. In Detroit, WWJ has been a consistent industry leader. Case in point: It was the top-ranked local station in April, and No. 2 in both May and June.

In the early years, most radio stations banked on variety, with dollops of news, weather, music, talk and so forth. But by the mid-1970s, WWJ started to move to an all-news format (though advertisers would insist the station keep Allison's hugely popular "Ask Your Neighbor").

Howard said the switch to all news was met with considerable skepticism.

"The whole town laughed," he said. "Where are you going to get news for 24 hours a day? They couldn’t fathom it. But WWJ proved them wrong."

From across the river at CKLW, newscaster Joe Donovan was watching.

"WWJ was switching from a kind of nothing special, dog’s breakfast format," he said, "into a real, dedicated all-news station. I was fascinated by that, and luckily, the station recruited me."

Donovan was the first of a wave of Windsor migrants that included Byron MacGregor, Grant Hudson and Don Patrick, who brought some of CKLW's "20/20 News" personality with them — what auto reporter Gilbert summarized as "the big voice and the rapid-fire style."

Jayne Bower, now at the Screen Actors Guild / American Federation of Television and Radio Artists union (SAG/AFTRA), was the afternoon-drive anchor at WWJ for 21 years until 2015, and was a hard-core Donovan fan.

"Joe had a remarkable style. When his voice came over the air," she said, "you had no choice but to listen. That’s the kind of presence he had. And if you know the old CKLW, their newscasters practically jumped out of the radio at you."

All the same, Donovan said, they tempered their rock 'n' roll bravado for WWJ's "much more sedate audience and responsible type of format." Still, some snuck through.

Donovan cites 1977 as the year the station completed the transition to all news. Today it's one of about 10 other all-news stations nationwide.

Rich Homberg, president and CEO of Detroit Public TV, was WWJ's general manager from 1996-2008, and calls it one of the best jobs he ever had. He completely embraced the all-news format.

"We had a deal in the newsroom," Homberg explained. "I always said, 'We own now: Now news, now sports.' Everybody worked incredibly hard. Everybody. They're terrific people," he said of the current staff. "They have a soul, and they love what they're doing."

Indeed, everyone connected to WWJ agrees it's a challenging gig.

"It's a gritty news machine," said Jasina, who anchors from 5-10 a.m. "I do a lot of writing. I do reporting. We all do that. People say they can't believe how hard we work. And it's true. We work, believe me."

Public-relations executive Matt Friedman, who began his career at WWJ as an intern during college, has a term he likes for the radio station: "Boot camp for broadcast news."

But even with the all-news format, news director Rob Davidek thinks the station still maintains radio's unique hold over its audience.

"People wake up with us," he said. "We're part of the family. I think sometimes we don't realize the impact we have on people's lives day after day."

Jasina called herself "a newspaper addict," but noted that with radio, you get an intimate connection that's harder to establish with newsprint.

"You not only get the news," she said, "you get this person — you get their voice."

And that is one reason she thinks radio will not just survive, but thrive in the future.

"I think radio can really just continue on," Jasina said, "because it's so personal and so lovely. It's just lovely communication."

But back to that all-important question whether Detroit can lay claim to being the nation's first commercial radio station. Disputed both by Pittsburgh's KDKA and KCBS in San Francisco, it mostly comes down to a matter of technical definition.

KDKA got its federal license a few months before WWJ in 1921, and that's its line in the sand. But 8MK, as WWJ was known in 1920, was on the air with an amateur license well before Pittsburgh.

"It's my understanding KDKA was the first federally licensed broadcaster," said Davidek. "We always joke that we went rogue and started before we had permission. It was like, 'We're going to try this. Hey! It worked!'"

Competition between the two claimants was once fraught. Time Magazine got its hand slapped in 1945 when it reported that the National Association of Broadcasters had declared WWJ to be 10-and-a-half weeks older than KDKA.

Clearly worried about blowback from Pittsburgh, the NAB President J. Harold Ryan wrote Time to complain they'd just put out information, without taking a stand. "To imply that the mere reprint of a chronology amounts to a 'final decision' on a disputed date of history," he wrote, "is manifestly unfair."

The apology didn't win him much. KDKA's parent company still went ahead and pulled all its stations out of the organization for eight years.

For its part, KCBS was on the air occasionally for years before 8MK, but got its federal license after both of the other stations.

Donovan dismisses KCBS before 1920 as just a "ham-radio" operation.

"People had been experimenting with radio since the 1880s," he said, "but broadcasting, with paid employees bent on creating a new medium, was born in Detroit, the Motor City."

mhodges@detroitnews.com

(313) 815-6410

Twitter: @mhodgesartguy