Once-rejected Bob Dylan photos find home at Grand Valley State

Gregg Krupa

Gregg Krupa

The editors of Look thought Bob Dylan looked too unkempt, with his tousled hair and his beatnik garb.

So, Look, which in 1964 was the second-largest general circulation magazine in the country, killed Douglas Gilbert’s photographic essay on the singer-songwriter.

The editors ignored the recently hired 21-year-old staff photographer from Holland, Michigan, and Michigan State University, who told them Dylan would make it big.

“Their words were, 'too scruffy for a family magazine,'” said Gilbert, now 78, who recently contributed those photographs of Dylan and thousands of others on other subjects to the Grand Valley State University Art Gallery in Allendale.

“His hair, his clothes, you know, just weren’t acceptable,” Gilbert said, recalling the disappointment of 56 years ago, and a different era of tastes and propriety.

“Which was pretty much nonsense, and people were angry about it,” including Dylan, his managers and his friends, like the folk singer Joan Baez.

“That’s what you get for being part of a corporation,” Gilbert said. “They had that right to do that. And they did it.”

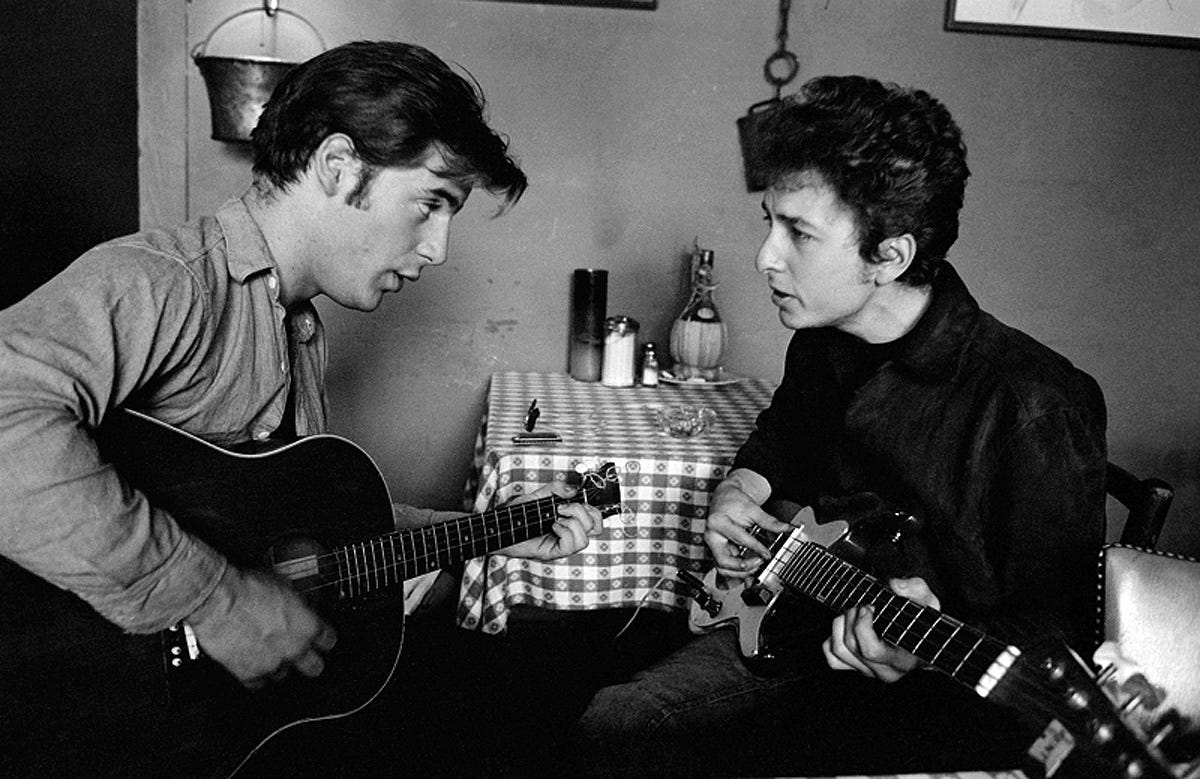

Lost to the readers of Look were Dylan in jam sessions with fellow singer and songwriter John Sebastian, teaching Allen Ginsberg how to play a harmonium — with which the beat poet had recently returned from India — and hanging out in two of the institutions of the beatnik era: The Village Bookshop and a tavern, the Kettle of Fish, in lower Manhattan.

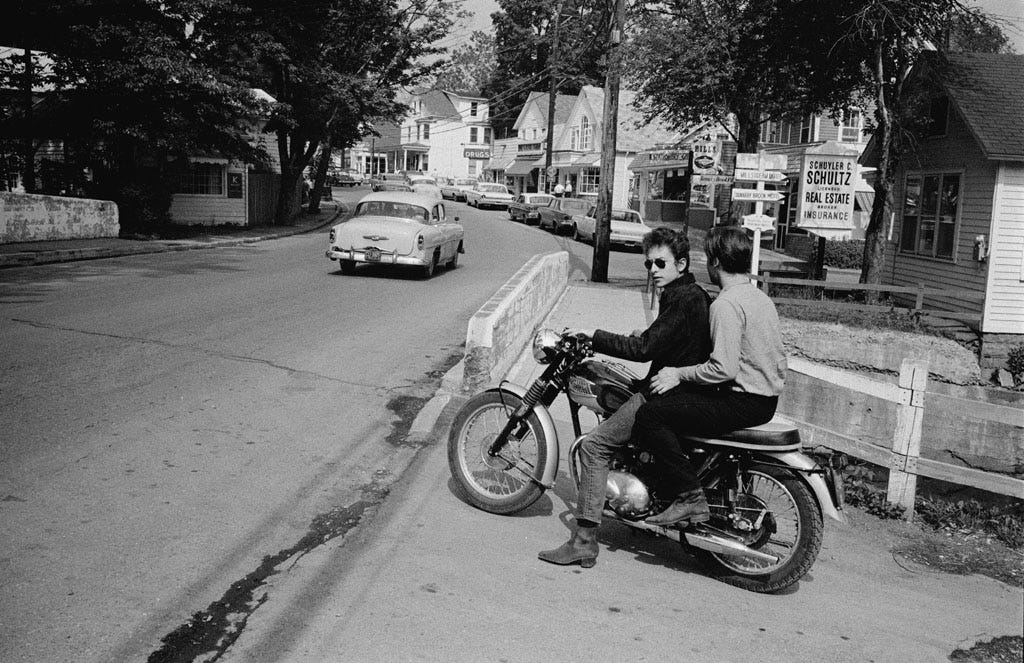

But now a large collection of Gilbert’s photographs of the 23-year-old Dylan, going about his daily life in Woodstock, New York, and Greenwich Village, are available for viewing through the Grand Valley art gallery.

Currently on display, there are Gilbert’s photographs from Italy that were also part of some 2,000 images in the Douglas R. and Barbara E. Gilbert Collection.

Some of the shots of Dylan are available online, and all by appointment at the museum.

Nathan Kemler, interim director of the Grand Valley Galleries and Collections, said it is the most comprehensive collection of photographic images the university has received.

“It’s a very large gift,” Kemler said. “We’re still counting it. But it is going to be close to 2,000 images.

“There are some musicians and celebrities that he photographed, things like the Bob Dylan photographs and things like Simon & Garfunkel and Iggy Pop.

“But he also did some other really interesting things, like about wilderness,” Kemler said. “He did this great series about light and shadow across the Italian architectural landscape. And he went into areas like, in the '60s, going into a school in New York where you had children with autism, at a time when autism wasn’t really understood.”

It is an accomplished oeuvre, for a noted photographer and artist.

Yet Gilbert can still remember the disappointment of the Dylan pictorial.

In eighth or ninth grade, Gilbert saw a friend and classmate do some show-and-tell with photography paper and chemicals the boy had brought to class. It left Gilbert fascinated with the developing process and taking photographs.

“So I went home with him after school so he could show me some more of this stuff,” Gilbert recalled in a phone interview from his home in Grand Haven.

“He ended up giving me a pile of papers and chemicals and things that he got from his uncle for nothing. His uncle worked at Eastman Kodak. So he got all of the expired paper and chemicals he wanted.”

Gilbert got a camera. His father, Russell, built him a darkroom in their basement.

At 14, he was developing his own film, making prints and selling stuff to the local paper, the Holland Sentinel.

Eventually, his photographs of athletic events and things as mundane as construction sites were published in the Grand Rapids Press and the Detroit Free Press.

His teenaged networking put him in touch with Phillip Harrington, eventually a photographer of considerable notice, who was then on staff at Look. Harrington told Gilbert of the internship for young photographers at the magazine.

Gilbert secured the internship. His work was so impressive, Look hired him immediately after graduation.

By then, Gilbert had met the 12-year-old younger brother of a friend of a girlfriend.

The 12-year-old called him into a room, showed him some photographs of Dylan and played his music.

It was 1963.

“And he said, 'you’ve got to hear this guy,'” Gilbert recalled.

“So he put the first album on (“Bob Dylan”), which was the one he had. And I said, 'I’ve never heard anything like that.'

“And, he said, 'Well, that’s right.' And he said, 'This guy’s going to be really big. Just watch it,'” he said.

“I picked up all of his albums that were out and began listening to them. And I had some things he had written,” Gilbert said. “And I thought, the kid’s right: Pretty amazing stuff!”

When he joined the staff at Look full-time, Gilbert said, he suggested a story on the recording artist.

“And they said, OK, we don’t know who he is. But go ahead.”

In late June 1964, Gilbert traveled upstate, to Woodstock, then a small, relatively anonymous town, where Dylan spent some time.

“He was enigmatic,” Gilbert said, repeating one of the most common observations about the nascent songwriter and performer, who was poised on transcendent fame. “But not yet to the point where he was cutting everyone out who he had not approved of beforehand.

“In reflecting on it, I’ve often thought that it was probably that he was rising, and he hadn’t quite broken the really big time, yet. And I have a feeling his management said, aha, here is the break!

“We can get him in that magazine and that’s going to really make him much more known,” Gilbert said.

He shot photographs of Dylan and Sebastian jamming on their guitars in the corner of a restaurant, of Dylan and friends at breakfast in his manager’s home, of Dylan and Ginsberg puzzling over the harmonium.

“He liked to know what was out and readable and had some real content, in books,” Gilbert recalled. So he shot lots of photographs of Dylan in The Village Bookshop, on Eighth at MacDougal in New York.

Among those in Dylan’s entourage in those days was another native of Minnesota, after whom Dylan styled himself, Jack Elliott.

Known by the state name Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, he sometimes introduced a song by Dylan as “written by my son.”

“We went across the street from the bookstore almost, to the Kettle of Fish, which was one of their favorite hangouts,” Gilbert said of the legendary West Village tavern.

“It was a bar, with tables and all. And about five of us gathered around a table and there was drinking and talking and telling stories and laughing and slowly becoming looser and looser.

“I have a photograph of Dylan in which he has hung an empty picture frame around his neck, and he’s obviously drunk and he was looking right at me, and he was saying, 'go ahead, take the picture of me. It’s already framed.'"

Dylan and Joan Baez saw the photographic essay, as it was laid out on the storyboards in the office at Look.

It was before the editors made the decision to kill the piece.

“I was coming back from lunch, and I didn’t realize they were looking at it, at that point,” Gilbert recalled.

“I came up to the door of the building and here were these two people kind of huddled in a corner, standing. And I recognized Dylan right away. And I asked if he had gone up to look at the story.

“And he said, 'Yeah.' And I said, 'What did you think?'”

Gilbert imitated a garbled, incoherent, barely audible response from Dylan that amounted to mumbles.

“Which was pretty standard for: You figure it out! But, he wasn’t upset. He was OK with it.”

After he found out the piece would not be published, Gilbert said he considered quitting, even though he was less than a year into his career.

A young guy from Holland and Michigan State learned some early lessons about the real world.

Or, at least, what passes for it.

“I learned a lot about publishing, especially nationally, in that time, and the values and the non-values and the maneuverings,” he said.

“And it was all pretty snaky.”

gkrupa@detroitnews.com