Redistricting plan seeks fair voting boundaries, but foes say it worsens problems

Beth LeBlanc

Beth LeBlanc

Of the three ballot initiatives voters will consider Tuesday, perhaps none has been more hotly contested or more closely watched than Proposal 2.

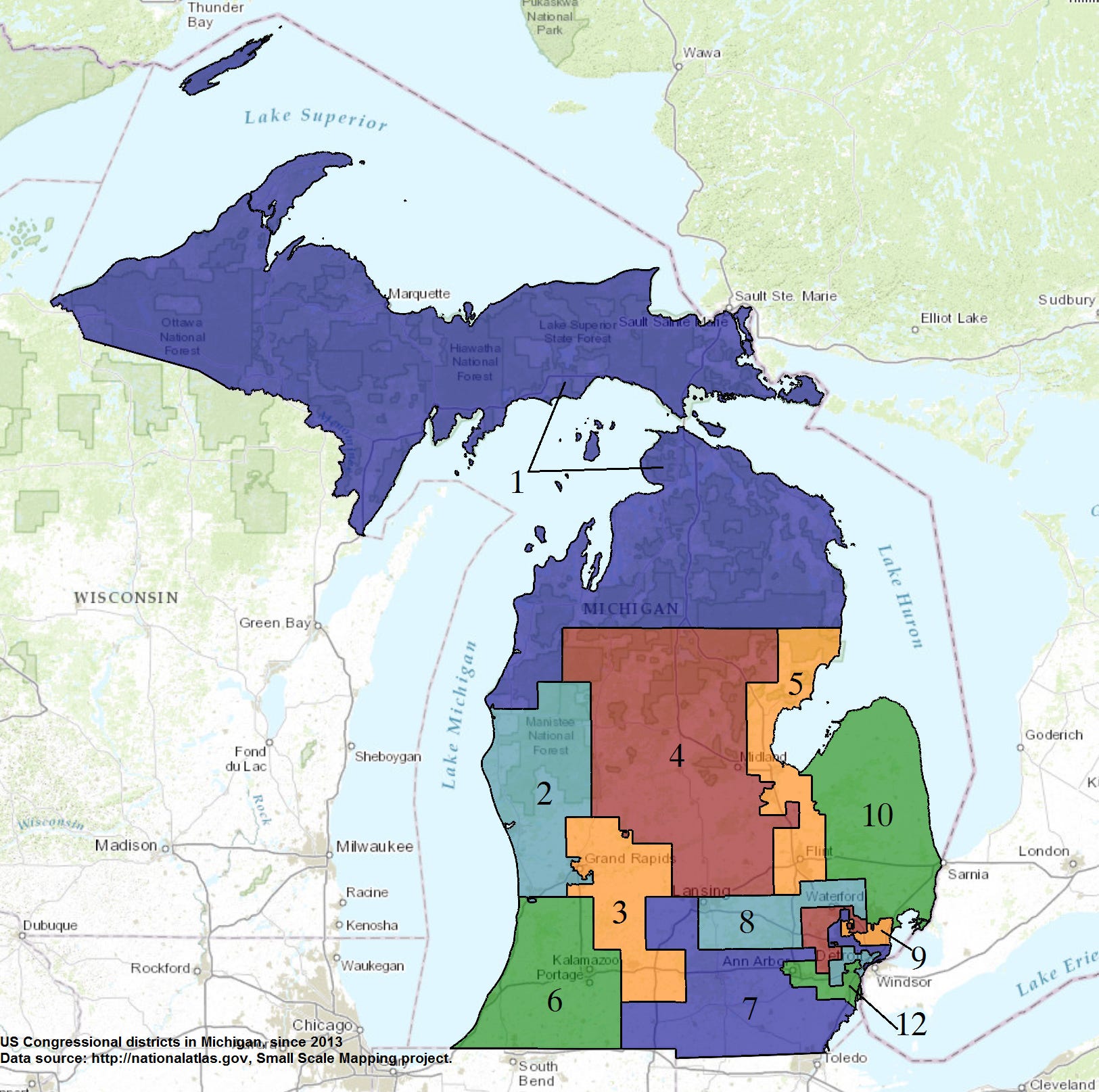

The proposed constitutional amendment would ax Michigan’s current redistricting process — in which the party in power redraws legislative and congressional district boundaries every 10 years — and hand that responsibility to a 13-member commission made up of four self-identified Republicans, four Democrats and five people not affiliated with any party.

The proposal seeks to combat gerrymandering, the manipulation of political boundaries to ensure a certain party dominates in elections. But critics contend the ballot measure would given too much oversight power to a partisan secretary of state, among other complaints.

The proposal has garnered support from several celebrities and politicians and received roughly $13.8 million in contributions from late July through late October.

“We started this to unite Michiganders,” said Katie Fahey, the 29-year-old executive director and founder of Voters Not Politicians. “Our political system is rigged right now. It’s not working for the benefit of the voters.”

Republicans have drawn the lines during the last two redistricting efforts.

More than $10 million of those contributions were from outside, left-leaning advocacy groups, a detail denounced by opponents who have argued that the initiative was a liberal Trojan horse to form districts favorable to Democratic candidates.

Opponents also argue the proposal lacks any caps on spending; that the commission selection process limits members to political neophytes, and that the sheer length of the proposal opens itself to misinterpretation and unintended consequences.

“This is just substituting one set of potential problems with a much greater and costlier set of problems,” said Tony Daunt, who is leading the opposition committee and is executive director of the Michigan Freedom Fund.

Selecting the commission

At roughly 3,200 words, Proposal 2 would make a raft of changes to the constitution. The secretary of state would be tasked with processing applications for the redistricting commission and randomly selecting four Democrats, four Republicans and five independents to be on the panel.

House and Senate majority and minority leaders would have the option of vetoing up to five applicants each before the secretary of state makes the final random selections.

The proposal prohibits a wide swathe of applicants who in the past six years were candidates, elected officials, consultants to a political party, employees of the Legislature or registered lobbyists. It also bans close relatives of those individuals.

Commissioners would be paid at least 25 percent of the governor’s salary of $159,300 a year or $39,820. Commissioner salaries together with consulting, legal and administrative costs would tally up to at least 25 percent of the secretary of state’s general fund budget, or $4.6 million of the department’s $18.5 million current year budget.

The state Legislature and governor will have to approve the budget, Fahey said, and “every dollar spent will be made public.”

The proposal also requires the Legislature to sufficiently fund the commission “to carry out its functions,” so if the $4.6 million minimum were insufficient, “additional appropriations would be required,” the nonpartisan Senate Fiscal Agency wrote.

The commission would convene no later than Oct. 15, 2020, the year of the next federal census, and adopt a redistricting plan no later than Nov. 1, 2021, after a process that includes at least 15 public hearings.

The proposal would require districts to be of equal population, compact, geographically contiguous, reflect the state’s “diverse population” and municipal boundaries and not provide an advantage to any one political party. The final decision would require a majority vote or, failing that, commissioners would resort to ranked voting.

Initiative's supporters

Since Fahey, a Hillary Clinton supporter in 2016, launched the petition drive to get the proposal on the ballot, the plan has garnered a handful of notable supporters from former Republican Michigan House Speaker Rick Johnson to Democratic former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder.

In October, actor and former Republican California Gov. Arnold Swarzenegger campaigned for the proposal among tailgaters in East Lansing. Hoisting a sign that said “Terminate Gerrymandering!” Schwarzenegger applauded the initiative and touted a similar effort he supported as governor in California in 2008.

“That people even understand what redistricting is, is a miracle because the politicians for 200 years have kept it a secret,” Schwarzenegger told reporters.

Most people can understand the risks of having a political party draw the maps, said Citizens Research Council president Eric Lupher, but “everything after that gets into the minutiae of it.”

A June report by the non-partisan Citizens Research Council showed Michigan’s political maps fail several advanced tests of partisan neutrality. And emails released this year as part of a federal lawsuit to stop gerrymandering showed Michigan GOP officials in 2011 attempted to dilute Democratic voters by “cracking and packing” them into a smaller number of winnable districts.

Along with the celebrity status, the ballot proposal has drawn in a hefty number of contributions, raising more than $13.8 million between July 21 and Oct. 21. Roughly $10.6 million of the total came from left-leaning, liberal advocacy groups such as the Sixteen Thirty Fund and Action Now Initiative.

It was clear from the beginning that fighting the “rigged” system would cost millions of dollars, Fahey said, but the campaign also received more than 14,000 small contributions.

'Devil's in the details'

Attack ads have targeted the proposal’s uncapped expenses for the process, the complexity and length of the ballot proposal and the expected dearth of qualifications among commissioners. But the ads have not addressed the fairness of the current system.

“What we’ve got before us is a proposal we are focused on fighting and defeating,” Daunt said. “The conversation of our current system is one we’re open to having down the road.”

While supporters of the proposal can rely on “bogey man” messaging that highlights the evils of gerrymandering, opponents have had a harder task in conveying the nebulous details of the proposal, said Dave Dulio, chairman of the political science department at Oakland University.

“The devil’s in the details,” Dulio said, noting that “debatable” language in the proposed amendment could muddle the commission’s implementation and invite “a ton of lawsuits.”

“How this thing gets carried out is really when we’re going to know what the ramifications are,” he said.

Michigan Freedom Fund, which has ties to the DeVos family of west Michigan, has chipped in roughly $2.8 million of the opposition group’s $3.1 million in funding. The Michigan Chamber of Commerce last week donated $100,000.

When campaign finance reports revealed the liberal money pouring into the Voters Not Politicians coffers, opponents pounced on what they perceived as proof of the proposal’s partisan motives.

Supporters’ claims of non-partisanship are hypocritical, Daunt said, and the proposal’s aim is nothing more than “an attempt to hijack our cConstitution from out-of-state interests.”

eleblanc@detroitnews.com

(517) 371-3661