Senate Republicans vote to scale back Michigan minimum wage, paid sick leave laws

Jonathan Oosting

Jonathan Oosting

Lansing — Michigan Senate Republicans voted Wednesday to scale back minimum wage and paid sick leave laws over objections from Democrats, who argued the lame-duck maneuvers may be unconstitutional and undermine the will of voters who signed petitions for the initiatives.

The 26-12 votes came just hours after the Senate Government Operations Committee unveiled and quickly approved major modifications to the citizen-initiated laws, which legislators adopted in September in order to keep them off the Nov. 6 ballot and make them easier to amend. The measures now head to the House for possible consideration next week.

Amendments to the minimum wage law would slow the planned increase from $9.25 to $12 per hour, a rate that would not be reached until at least 2030 instead of 2022, and cap the minimum wage for tipped restaurant workers at $4 per hour instead of also gradually raising it to $12.

The revised paid sick leave law would exempt companies with fewer than 50 employees and halve the minimum hours that employers would be required to provide, from 72 hours a year to 36 hours a year.

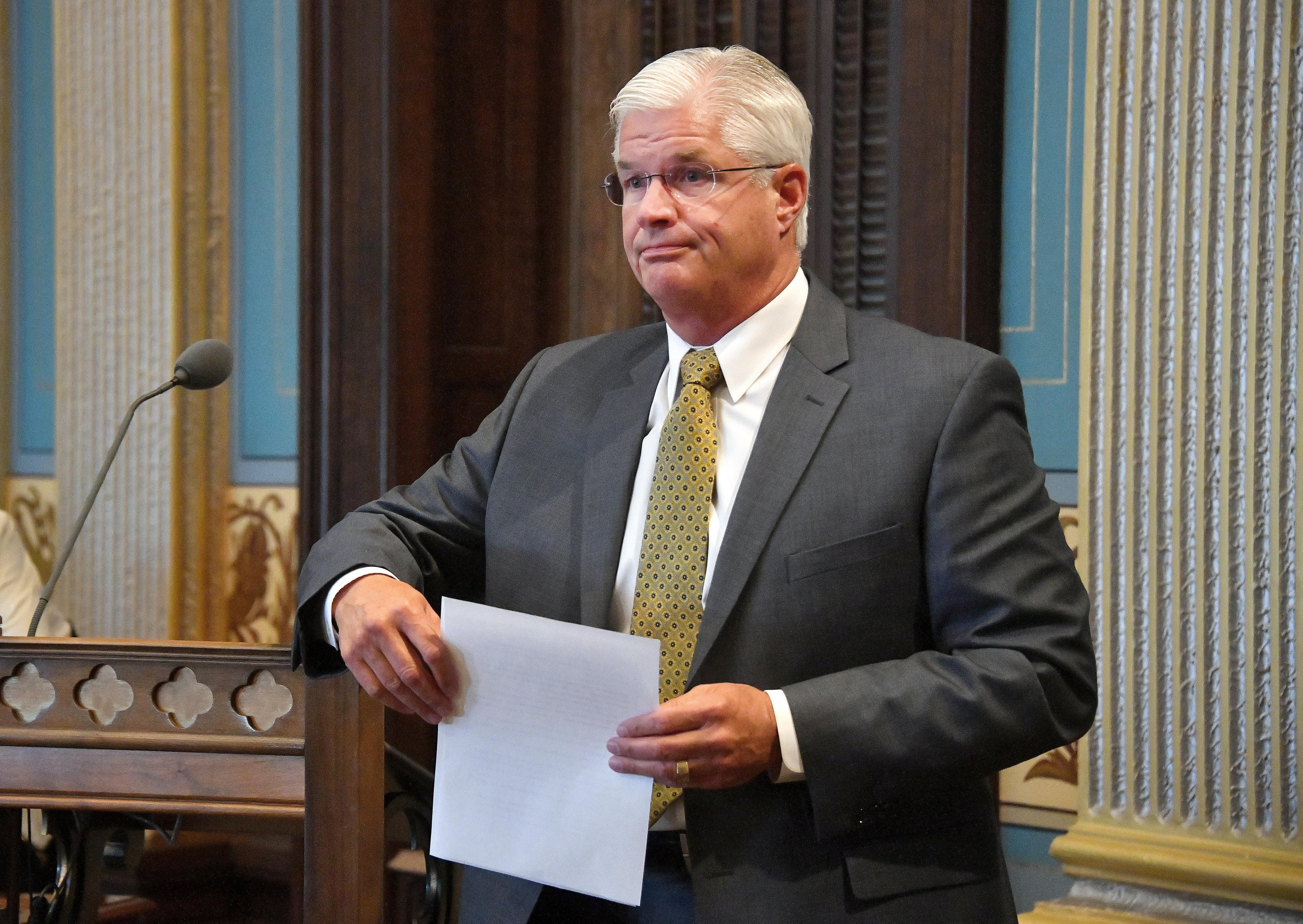

Senate Majority Leader Arlan Meekhof, R-West Olive, defended the legislative process as fair, telling reporters that business owners and other citizens urged modifications to "make sure Michigan continues on its economic progress."

"The voters know when they sign a petition that it comes before the Legislature before anything happens to it." Meekhof said.

But Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich, D-Flint, ridiculed what he called a "bait and switch" by Republicans, suggesting they rushed to enact changes to the laws before Democratic Gov.-elect Gretchen Whitmer takes office in January.

"I think one of the most troubling things is they dropped the bills the day after the election," Ananich said. "So obviously they had these bills in the works all summer long and didn't have the courage to show the voters what they were planning on doing."

Other changes to the paid sick leave law would slow the benefit accrual, requiring employees to work 40 hours to earn one hour of medical leave, down from 30 hours in the law. The bill would also eliminate “rebuttable presumption” for workers who allege inappropriate punishment and shorten a record retention requirement for employers.

“This maintains the spirit and the intent of the citizen initiative while removing ambiguities and requirements, which would have led to two things for certain: an increased incentive to not hire people, and a cacophony of lawsuits between employers and employees,” said sponsoring Sen. Mike Shirkey, a Clarklake Republican poised to become majority leader next year.

Ananich disputed the characterization, saying the revised bills come "nowhere close" to the spirit of petitions signed by voters who wanted a pay raise and greater ability to take care of sick family members. Republicans have used eight years of total control to support "corporations and people at the top," he suggested.

Danielle Atkinson, an activist who helped spearhead the MI Time To Care campaign, said the nearly 400,000 voters who signed petitions for the paid sick leave law “were not confused.”

“They knew exactly what they were signing,” she told lawmakers in committee. “They knew exactly what they wanted. And when they were signing, they told us their stories of their own chronic illnesses, of sitting with their sick child in the hospital.”

Business groups pushed for changes in the laws, which would not take effect until the spring. The paid sick leave initiative would create “great difficulty” for both employers and employees, said Charlie Owens, state director for the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

Unlike the petition, proposed amendments were developed with input from the business community, he said, arguing that employer costs for the mandate would impact employees.

“Workers will see cuts in pay, health insurance, retirement and other benefits, even including better sick leave policies in order to absorb the mandated costs,” Owens said. “Some employees will get the ultimate benefit cut: Their jobs.”

The Michigan Constitution allows lawmakers to adopt proposals initiated by petition drives, but some legal experts have said that amending an initiative in the same session it is adopted could be unconstitutional.

Doing so would violate “the spirit and letter” of the initiative process, then-Attorney General Frank Kelley, a Democrat, wrote in a 1964 opinion that has not been tested in the courts.

Pete Vargas, an organizer with the One Fair Wage minimum wage group, argued that “gutting” the law during the lame duck session is “blatantly unconstitutional and will likely lead to costly, time-consuming court challenges.”

It’s also “just plain wrong,” he said, predicting it will sour voters on the political process by increasing cynicism “that has been growing in Michigan and national politics for far too long.”

Meekhof dismissed those arguments and expressed confidence the Legislature has the legal authority to amend the initiatives.

"There is nothing in the constitution that prohibits us from this kind of action," he said after the Senate vote. "Attorney General Kelly's opinion from 50 years ago doesn't even reference a case, doesn't reference the constitution. It's just his opinion."

The revised minimum wage law would raise the rate to $9.48 an hour in 2019 and then increase it by 23 cents each year, unless the state’s unemployment rate tops 8.5 percent. The legislation would cap the rate at $12 per hour and eliminate an existing mechanism for automatic increases based on inflation.

The initiative would have raised Michigan’s $3.52 rate for tipped restaurant employees to $12 by 2024. The amended proposal would instead raise the rate to $4 by 2030.

The legislation “preserves the goal” of a $12 minimum wage for most workers but addresses concerns from tipped employees who feared the law could have a “devastating impact on their earning ability,” said Sen. Dave Hildenbrand, R-Lowell.

The law could be an “Armageddon scenario for the restaurant and hospitality industry” by discouraging tipping, said Robert O’Meara of the Michigan Restaurant Association.

But nothing in the law would prohibit customers from tipping restaurant workers who earn a higher minimum wage, said Joel Panozzo, who owns the Lunch Box restaurant in Ann Arbor and supports the $12 minimum wage.

"We have a strong tipping culture in our restaurant despite paying a living wage," Panozzo told lawmakers. "Our clientele, knowing we pay a living wage, do not then tip less."

Sen. Curtis Hertel Jr., D-East Lansing, said he has heard concerns from tipped workers in his district and would be willing to consider amendments next year — but not in the current session.

"I will not support a blatant violation of our democracy, a violation of our Constitution," he said before the vote.

Sen. Tory Rocca of Sterling Heights was the lone Republican to vote against either measure in the Senate, where 25 of 38 members will leave office at the end of the year because of the state's term-limits law.

joosting@detroitnews.com