100 years after it sank, the freighter Huronton is found at bottom of Lake Superior

Jakkar Aimery

Jakkar AimeryAll souls were on board when the Huronton sank 100 years ago.

And all the souls were saved before the ship hit the bottom of Lake Superior, even the four-legged one.

It was man's best friend that spurred First Mate Dick Simpell into action a century ago, leaping upon the vessel's flooding stern to save the life of the crew's mascot and 18th member, a bulldog.

Over the summer, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society boarded the museum-owned, 47-foot, retired U.S. Army Corps research vessel the David Boyd and towed the museum's sonar towfish, hurled the device in the lake, and found, in the blanketed depths of Lake Superior, the Huronton.

▶ RELATED ARTICLE: Diving for answers: How warming water threatens Lake Huron's shipwrecks

Searching the water in grids, crews explored for days, with hopes that they'd add to the list of more than a dozen shipwrecks discovered in the last two years. And then unexpectedly, they saw something.

"We knew that we had a shipwreck; it was a reasonably intact-looking vessel on the sonar imagery as well, even though this vessel sank as a result of pretty dramatic collision," said Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society in Paradise, Michigan.

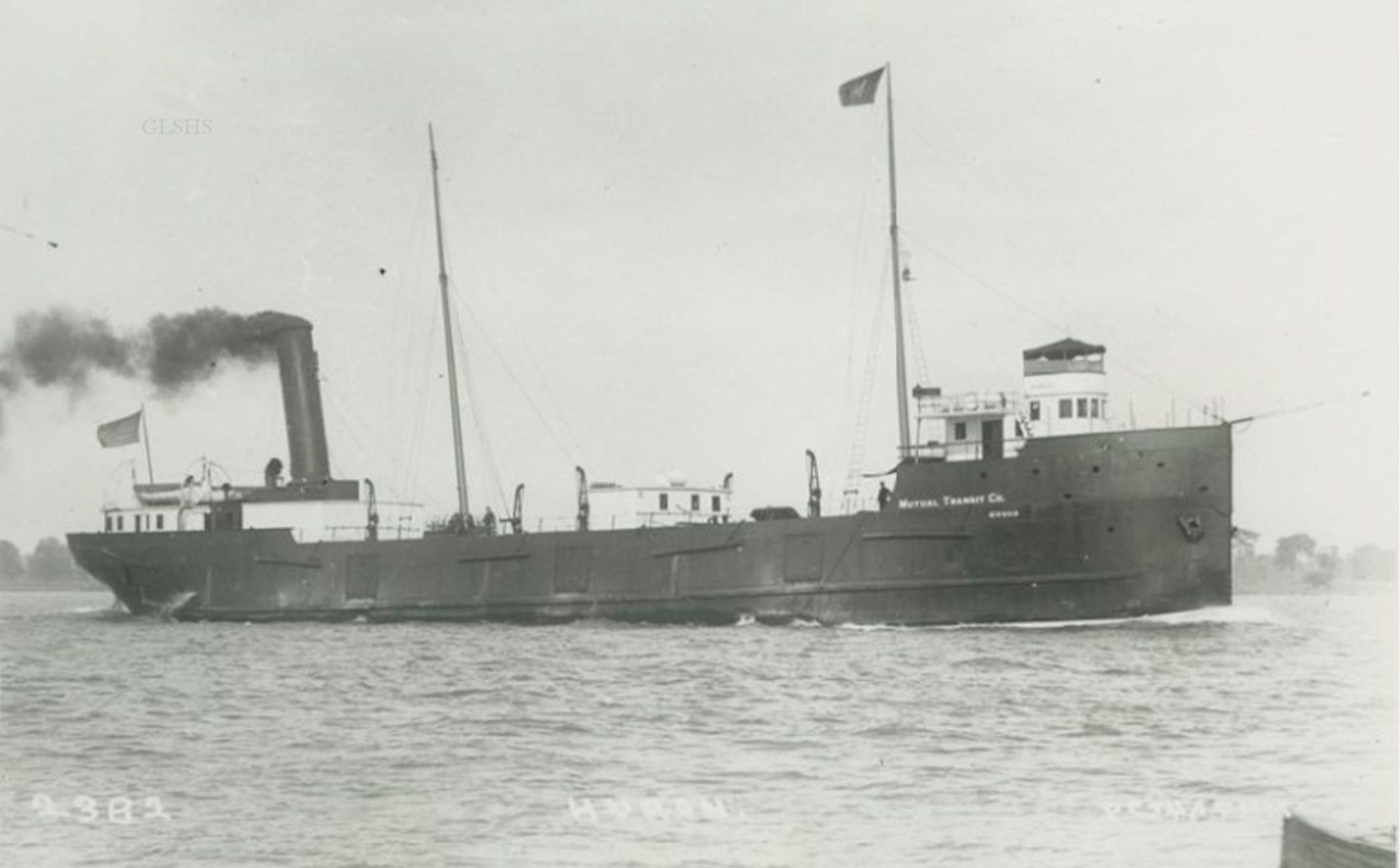

On Oct. 11, 1923, the Huronton, an empty, 238-foot-long bulk freighter, was making its way north, enveloped in the chilling, deep waters of Lake Superior.

Cloaked in dense fog and smoke plumes from nearby forest fires in the Upper Peninsula's east, a 416-foot-long, fully loaded bulk freighter Cetus was heading in the opposite direction, the Huronton in its path. With both ships traveling too fast for the conditions, the Cetus plunged into the Huronton, gashing a hole port side and locking the ships together.

"The fog is not unusual because we have fog up here all the time. But when you combine that fog with the smoke from a forest fire, it's just a hundred times worse," Lynn said. "Chances are, the captains on board probably couldn't see one end of the ship from the other."

The Huronton, according to Lynn, had previously been commandeered by the government prior to its purchase by a company in Toronto. It was used to transport sorts of war materials on the east coast during World War 1, he said.

Having his "wits about him," Cetus Capt. Webb Beatty kept the ship moving forward, plugging the hole that his vessel had made in the side of the Huronton, which created a window of opportunity for its crew to escape before the ship plunged 800 feet to the lake bottom, museum officials said.

Lynn said Beatty previously may have been aware of other incidents or collisions, where similar actions saved crews, prompting him to cork the gaping hole.

Eighteen minutes later, the vessel sank, about 20 miles northwest of Whitefish Point in the U.P., taking no human or canine lives with it, Lynn said.

Museum officials said the discovery brings to light that which is "truly a part of our past."

"Finding any shipwreck is exciting," Lynn said in an earlier statement. "But to think that we’re the first human eyes to look at this vessel 100 years after it sank, not many people have the opportunity to do that.

"Every so often, if we're lucky, there might be some little anomaly on the bottom of the lake, some kind of tiny straight line that we'll often want to go back and look at."

Turning the boat around to get a closer look, the crew observed details on the vessel, like the hole in its side, and they knew they found the ship.

The Huronton was spotted "extremely deep at 800-feet below the surface," as crews used a torpedo-shaped sonar towfish to inspect further, society officials said.

"The depth dropped on us from 300 feet to 800 feet," said Darryl Ertel, director of marine operations, in a statement. "And for us to keep a good sonar image of the bottom, we would have to let out a lot more cable or slow down.

"It was just a small, 800-foot hole and there was a little sliver in there that was a straight line, but (the ship) looked like the size of a thread. And because it was a straight line, I marked it as a possible target, 4 hours later, we come back on our way home to check it. And sure enough, it was a shipwreck."

Blanketed in the bowels of the lake, fragments of the Huronton could be seen partially intact, alongside the gashing tear on its flank where the Cetus struck.

Excluding about 200 shipwrecks that've been located within a nearly 100-mile stretch between White Fish Point and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in the U.P., Lynn said that a lot of them "quite simply just have been forgotten."

In an effort to raise awareness and preserve history, Lynn said the museum plans to further assess and document the wreck and collect information for an exhibit at the museum's Whitefish Point site, while preserving its remains under water.

"Eventually, this could be subject for an exhibit at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum and will certainly be a topic for programming in libraries, museums, schools and history conferences," Lynn said. "There's a lot of different ways that we can keep the history alive of this wreck, and I think there's any number of reasons why we would do that — it is a part of maritime history in the Great Lakes."

jaimery@detroitnews.com