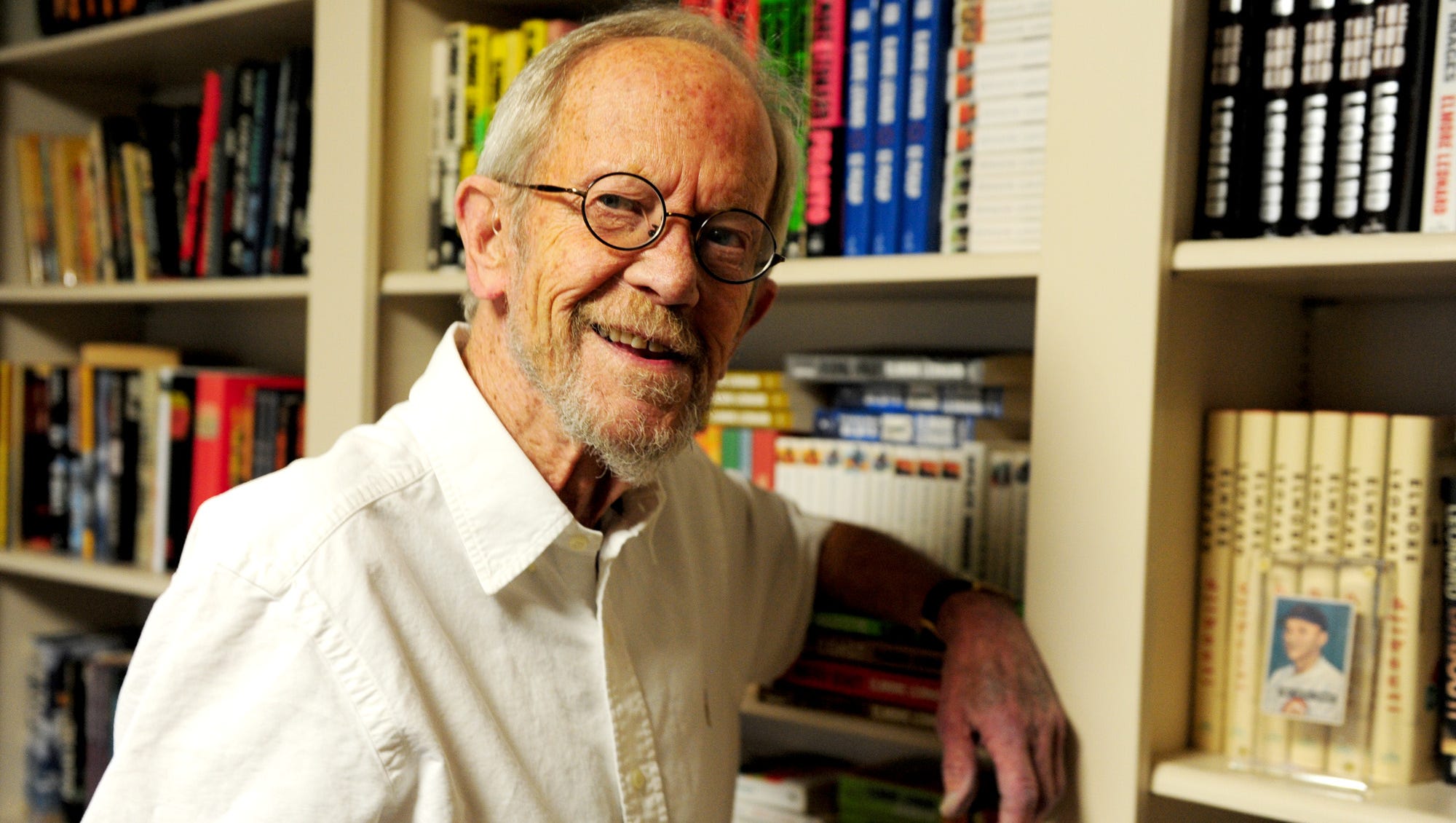

Elmore Leonard's ex-wife sues son, trust, firm over archive sale

Mike Martindale

Mike Martindale

Pontiac — It reads like a subplot to one of the late Elmore Leonard's own best-selling crime novels.

The author's ex-wife is suing his company, trust and her former stepson, claiming all three engaged in a secretive plan to sell off his archives after his death and cheat her out of a share of more than $1.1 million in proceeds.

The Bloomfield Hills couple’s 18-year marriage ended in a December 2012 divorce, and Leonard died in August 2013 at the age of 87. Leonard’s net worth, derived from dozens of published works, several which have been made into films and TV series over the past half-century, is estimated in the millions.

At issue, according to Christine Leonard’s complaint, are 150 banker’s boxes of manuscripts, unpublished stories and other Elmore Leonard materials, which she alleges were sold to the University of South Carolina for $1.15 million in February 2014.

According to Christine Leonard’s lawsuit, filed in Oakland County Circuit Court, the settlement agreement in the divorce entitled her to 21.25 percent of the sale of any of her ex-husband’s “literary works, manuscripts, drafts and other intellectual property.”

The agreement also states any and all transfers of income-producing assets, such as the archives, require her prior written consent, according to the lawsuit.

“I can’t talk about this yet,” Christine Leonard told The Detroit News recently when asked for comment on the lawsuit.

But in her complaint, Christine Leonard said she not only never consented to the sale, she was never informed of it. She alleges in August 2013, the same month as Elmore Leonard’s death, Peter Leonard “secretly arranged” to have his father’s archives transferred from Elmore and Elmore Leonard Inc.’s name to that of the Elmore Leonard Jr. Trust.

Her attorney, Geoffrey Wagner, said his client learned of the sale on the internet.

“It’s an agreement that has been violated,” Wagner said. “The (settlement) language is clear that she is entitled to any sales, and that hasn’t been done. We will also be trying to determine if there have been other examples where this has been done.”

Gerald Cavalier, who represents Peter Leonard, Elmore Leonard Inc., and the Elmore Leonard Jr. Trust, said the lawsuit is without merit.

“We will be filing a response within three weeks,” said Cavalier. “We expect the court will ultimately dismiss the complaint, which is actually a request to enforce an agreement.

“We have already had some meetings on this and don’t agree with their view of the law,” he said. “We don’t think they are entitled to any relief.”

Leonard is best known for his crime fiction novels popularized in in films like “Get Shorty” and “Be Cool.” His early popular writings in the 1950s were western short stories like “3:10 To Yuma,” which has been made into two films.

Tom McNally, dean of libraries at the University of South Carolina, said the Leonard archive, gathered with the help of the author’s family and his longtime researcher Greg Sutter, includes more than 450 drafts of manuscripts, short stories and screenplays, typed on his signature yellow paper.

The collection includes all of his 45 novels, magazine articles, notes, letters, photos and more – including an unfinished manuscript, found on his desk, which he was working on at the time of his death.

“We have director’s chairs from movie sets where he sat as his words were made into film,” McNally said. “Some of his typewriters and writing materials. Movie posters. Even sneakers.”

McNally said he wanted Leonard’s papers and called to invite him to visit the library to see how writers' archives are preserved.

During his visit, a few months before his death, Leonard was especially impressed with the collections of Ernest Hemingway and George V. Higgins, two of his favorite writers.

“We have several authors' archives, and he wanted to look at the writings of Higgins,” McNally said. “He was reading a manuscript of ‘Friends of Eddie Coyle’ and it almost brought him to tears. He was very moved."

Higgins was reportedly a major influence on Leonard for creating gritty dialogue for characters that could have grammatical errors and did not have to end in complete sentences: like the way people actually talk.

McNally said he heard from Leonard’s family that on the flight back to Michigan from the library visit he told his son, Peter, that was where he wanted his archives to go.

More than 50 researchers from around the world have since spent countless hours with Leonard’s treasured archives, McNally said, including an Italian who had no interest in crime fiction but wanted to see everything there was about “3:10 To Yuma.”

“We are proud to have his archives,” McNally said.

Leonard’s papers are in good company. Besides other crime fiction writers like Dashiell Hammett (“The Maltese Falcon”; James Ellroy (“The Black Dahlia”), the library has the papers of novelist Pat Conroy (“The Great Santini”). It has preserved rare manuscripts from other countries and periods, including medieval times.

McNally would not discuss specific purchases but said an author’s works usually start at “$1 million and up.” Some are even gifts.

The South Carolina library maintains the largest collection of Hemingway’s personal papers in the world. Among the collection is a first-edition copy of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” inscribed to Hemingway by Fitzgerald.

“That one book is valued at more than $600,000,” he said. “Of course most of these materials are priceless.”

McNally said all of the archives are carefully stored and maintained, and when they are reviewed, it's under the watchful eyes of employees and video cameras.

“Researchers come here for the love of the writings and love of the authors,” he said. “They especially like reviewing the working notes on manuscripts where they can view what words the author selected to replace the words they crossed out. It’s like candy to them.”

The Leonard collection includes notes on how the author originally toyed with setting “Get Shorty” in New York City’s fashion district.

“The collection is important because it will lead to the writing of books and articles about Elmore Leonard and his contributions to writing,” said McNally. “And it will be here forever.”

mmartindale@detroitnews.com

(248) 338-0319