He's an accused killer and mentally ill — and Michigan can't find a place for him

Karen Bouffard

Karen BouffardDetroit — An autistic, severely mentally ill 19-year-old was discharged from the Wayne County Jail to a no-man's land last month, suspended between hospital emergency rooms and uncertain placement in adult foster care or a state psychiatric facility.

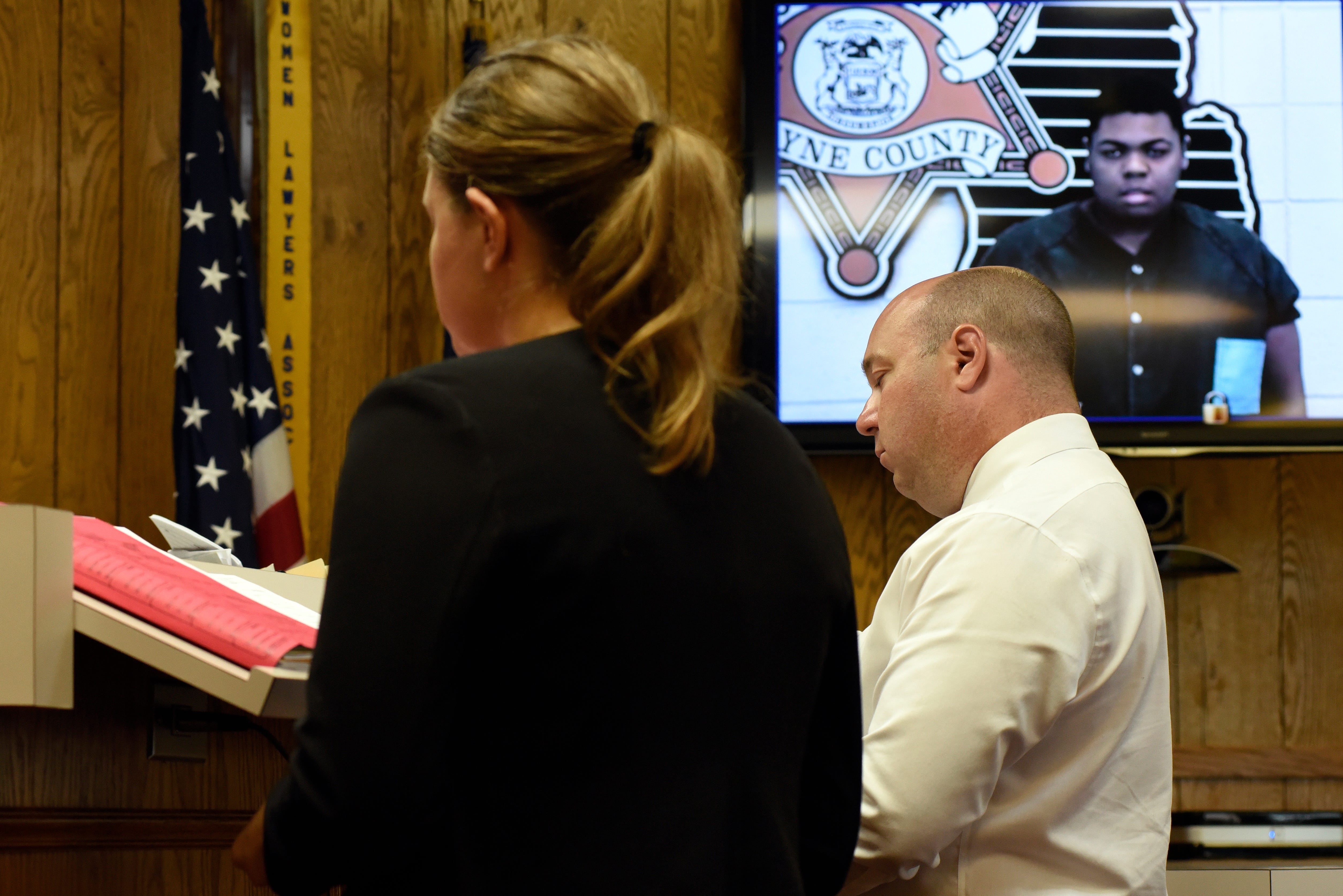

Darian Michael Smith-Blackmon spent six months in jail on a first-degree murder charge before he was ruled incompetent to stand trial. Despite a track record of assaults in adult foster care homes, he has not been placed in a state psychiatric hospital.

His case illustrates Michigan's struggle to care for its most difficult mentally ill residents while preventing them from harming others.

See the full "Healing Justice" report | About this project

“This is systematic malpractice,” said Tom Watkins, the former president and CEO of the Detroit/Wayne County Mental Health Authority and a former state mental health director, when told the details of Smith-Blackmon’s case.

The intellectually disabled teen has lived in group homes since the age of 9 due to unmanageable symptoms of autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Smith-Blackmon was taken to the Wayne County Jail on March 22 after he was accused of killing a fellow resident at Woods Care Home, an adult foster care facility in the city of Wayne.

In a display of hair-trigger temper, the 6-foot, nearly 300-pound Smith-Blackmon allegedly punched and kicked the elderly man to death over a minor exchange of words, injuring two staff members who tried to intervene, according to the Wayne police report.

John Bagget, who suffered from "mild retardation and schizophrenia," died of his injuries on April 22. The Detroit News couldn't reach his next of kin.

Though Smith-Blackmon was ruled permanently incompetent to stand trial on Aug. 27, he could face trial in the future under Michigan law if he is ever deemed competent.

His lawyer and family members, as well as Smith-Blackmon himself, expected he would be admitted to a state psychiatric hospital for treatment. On Sept. 17, his attorney received an email from Wayne County Assistant Prosecutor Elizabeth Dornik saying, "I understand from my office he was civilly committed yesterday" — meaning committed to a state psychiatric hospital.

But Smith-Blackmon was discharged from jail late in the evening that day and taken to the emergency room at Detroit Receiving Hospital, said Bill Amadeo, an Ann Arbor attorney.

Four days later, the hospital discharged him to a group home. But he was returned to the hospital within hours, said the teen's mother, Melvina Smith of Romulus.

"He was extremely manic and pleading to be sent to a hospital," Smith said in a text to The News. "Later last night, he had been restrained and given multiple injections to calm him... .

"I received over 20 calls from him yesterday. I am so scared for him."

People suffering from bipolar disorder have swings between periods of high energy and elation known as manic episodes, and extremely sad and hopeless periods of depression. Patients with schizophrenia have symptoms that can include hearing voices or thinking others are trying to hurt them.

"He literally kills somebody and the system feels he’s incompetent to be in jail — so they put him in an emergency room?” Watkins said when told of Smith-Blackmon’s case. “If this isn’t an alarm for a system that is not working, I don’t know what is.”

Adult foster care homes typically provide little more than a bed and meals with limited supervision, so sending him back to the same kind of setting where he allegedly killed a man is the definition of insanity — “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result,” the former state mental health director said.

Under an order signed by Wayne County Probate Court Judge Lawrence J. Paolocci on Sept. 16, Smith-Blackmon is to receive assisted outpatient treatment for no longer than 180 days. The order permits hospitalization of up to 60 days, but doesn't require it.

Two psychiatrists who examined the teen certified Smith-Blackmon is mentally incompetent to stand trial and likely to injure others in the future. One recommended hospitalization, while the other called for the combination of hospitalization and outpatient treatment, according to court documents.

Both the defense and prosecution agreed to the plan, Paolocci noted. Asked if the lack of a state hospital bed was a factor in Smith-Blackmon's not being committed to a psychiatric facility, the judge said he didn't know.

"That may be true," Paolocci added.

Amadeo, the attorney, said he needed to get his client out of jail.

"You take anybody in his condition and put them in there, it’s going to be a death penalty," he said.

Home placement mystery

Questions remain about Smith-Blackmon's original placement at Woods Care Home, where the fatal assault occurred in March. The low-security facility houses mostly elderly, developmentally disabled people who can come and go as they please.

Could Bagget's life have been saved had a bed been available at a facility better-equipped for people, like Smith-Blackmon, who require a higher level of security and expertise?

Court records reveal Smith-Blackmon had assaulted people at two previous adult foster care facilities. Smith said her son had a history of lashing out if he felt provoked.

Gloria Hamilton, the owner of Woods Care Home, told police Smith-Blackmon had been at her facility for about a month after being placed there "under an emergency circumstance" following a "similar" assault at his previous group home.

He had lived in four different adult foster care homes in the short time he had been an adult, receiving in-patient psychiatric care for psychosis at local hospitals in between placements.

The Woods Care placement was arranged by Development Centers, a nonprofit agency under contract with the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority, the community mental health provider for the county, Smith-Blackmon's mother said.

The authority wouldn't confirm Development Centers' involvement because of privacy laws. Calls to Development Centers were not returned.

Asked if Development Centers tried to find a more secure facility for her son, such as a state mental hospital, Smith said: "Not sure. It was always me insisting on things. ... They would all say finding a home was hard, no beds in hospitals, and then instantly they find any home to put him in."

Shortage of beds

In Michigan, mentally ill people who can't live independently or with family members are most likely to live in adult foster care homes. But it can be challenging to find an adequate placement for a difficult-to-manage patient, or the small fraction who can be dangerous.

Most of Michigan's state mental institutions were shuttered in the 1990s under then-Gov. John Engler, reflecting a national trend. As of the end of September, 138 people were on a waiting list for treatment at a state mental hospital, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

Meanwhile, a lawsuit winding its way through the courts alleges that Michigan individuals deemed not guilty by reason of insanity "remain in state psychiatric hospitals for far longer than the maximum sentences they could have received had they simply pleaded guilty to relatively minor offenses." This situation occurs even after their conditions have stabilized and they no longer pose a danger to the public, according to the suit.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, but it was denied. Detroit U.S. District Court Judge Paul Borman ruled Sept. 20 that the lawsuit can proceed.

Michigan operates five inpatient psychiatric hospitals, including the Center for Forensic Psychiatry, which provides diagnostic services to the criminal justice system as well as treatment for defendants found incompetent or not guilty by reason of insanity.

Michigan added 195 state psychiatric hospital beds between 2010 and 2016, increasing its total from 530 to 725.

But the state still had the 46th fewest in the nation with 7.3 state psychiatric beds per 100,000 residents, according to a 2016 study by the Treatment Advocacy Center, a Virginia nonprofit that works to reduce barriers to care for the mentally ill.

No state in the country met the group's recommended minimum of 50 state psychiatric beds per 100,000 people. The study counted only the beds at state-run institutions — often the last resort for severely mentally ill people, who may lack medical insurance or be difficult to manage.

States across the country are struggling to keep pace with an increasing number of mentally ill criminal defendants who require competency evaluations, though 2% of people with serious mental illness commit major crimes, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center.

Defendants who are jailed while awaiting treatment after being declared incompetent to stand trial wait an average of 127 days for forensic evaluation at a state mental hospital. But it typically takes months in jail to complete the process that leads to a judgment of incompetency.

Those who are jailed pending a forensic competency evaluation can languish as long as a year while awaiting admission to the state Center for Forensic Psychiatry in Ypsilanti, though three-quarters of competency evaluations are completed within 60 days as required by Michigan law, according to the state.

"We do have a wait list for people coming in under that legal status, (but) there are outliers," said Debra Pinals, medical director for behavioral health and forensic programs at the state Department of Health and Human Services. "The average is much shorter than that."

The state is working with prosecutors, judges and community mental health providers to create strategies to ease a logjam of requests for psychiatric evaluations even in misdemeanor cases, Pinals said. Initiatives are underway in several counties.

His own guardian

Complicating Smith-Blackmon's case, he was his own legal guardian, the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office confirmed. Though developmentally disabled and severely mentally ill, he was legally responsible for his own care.

Smith said she applied for guardianship earlier this year, though it was never completed. None of the professionals involved in her son's care raised the issue, she said.

"I was the one inquiring and (Smith-Blackmon's case manager) at the Development Centers wanted me to wait while they gathered paperwork to assist me in that process," Smith said. "... I kept asking how much longer and unfortunately, it did not happen."

For Smith, her son's situation has been heartbreaking. It took eight days for Smith-Blackmon to be given psychiatric medications at the jail after his arrest and about a month before he was allowed a shower, she said.

"I know there is nothing anyone can do now but I fear my son will not make it," Smith said in a July 12 letter to Amadeo, the attorney who represents her son.

Amadeo said his access to Smith-Blackmon was limited at the Wayne County Jail. The teen spent most of his time there in a psychiatric unit with one small room where attorneys can meet with their clients.

"I saw him briefly three or four weeks ago; he didn’t understand what what going on at all. I tried to see him again today unsuccessfully," Amadeo told The News in mid-July.

As of Wednesday this week, Smith-Blackmon was still at Detroit Receiving Hospital awaiting placement in an adult foster care home. He also has been treated for a kidney ailment, his mother said.

Smith, who talks to her son by phone several times daily, said his state of mind has improved with adjustments to his medications and he "is not in a current state of suicidal or homicidal thoughts."

"I am praying it takes (a) bit longer actually," she said of her son's hospital stay.

Smith, who still wants guardianship, said she dreams of one day caring for him herself with help from in-home mental health workers.

"Lofty goals, but my mission and reason for working," she said.

But Smith-Blackmon sounds like he needs more intensive care, said Watkins, the former state mental health director. More appropriate settings do exist outside the state mental hospital system but are expensive, he said.

“Very few people should live in a hospital all their life," Watkins said, "but certainly somebody like this is going to need something more intensive than an adult foster care home."

“Healing Justice" is a Detroit News project made possible through a fellowship with the Association of Health Care Journalists funded by the Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit foundation focused on health.

kbouffard@detroitnews.com

Twitter: @kbouffardDN

NEXT ARTICLE: Killing prompts care, not prison in Norway