Bankole: After bankruptcy, Detroit retirees feel deprived

On July 18, 2013, Kevyn Orr, Detroit's former emergency manager, after failing to reach an agreement with union workers and creditors over how to address the city’s $18 billion debt, placed the city into chapter 9 bankruptcy protection.

That decision made Detroit the largest municipality in U.S. history to face that level of financial reckoning. And Wednesday will mark the five-year anniversary of that monumental and complicated act regarding the future of the city.

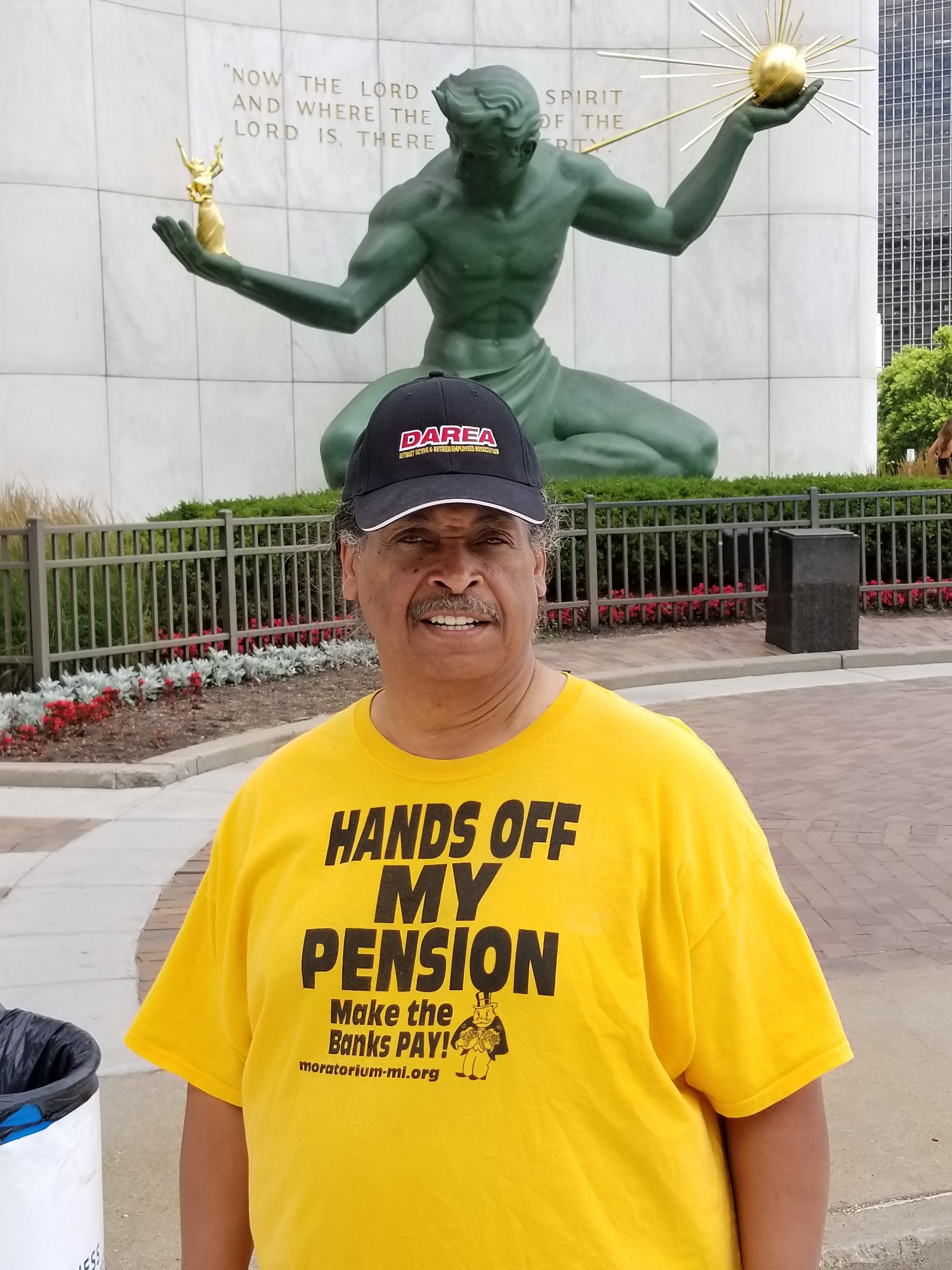

“The bankruptcy is the single largest devastating event the city has had to face since the 1967 riots because it affected so many people and it dramatically changed the worth of the city,” said Bill Davis, president of Detroit Active and Retired Employee Association.

Days leading up to the bankruptcy, Davis and a group of retirees got together wondering what they could do to save their hard-earned pensions.

They were hoping that no matter what happened their pension would be saved since it was protected under provisions in the Michigan constitution.

Davis, 60, who gave 34 years of service to the city working at the Waste Water Treatment Plant on W. Jefferson until he retired a year before the bankruptcy, was getting nervous.

He had been sensing the direction the city was going after Gov. Rick Snyder tapped Orr, a Jones Day bankruptcy lawyer, to oversee the city's financial destiny at that point.

“Many city retirees and workers stayed in the city with their dollars to help our local economy,” Davis said. “I think the bankruptcy has made poverty worse for many of them who are living on the edge now and hoping that their kids and grandkids can keep them out of poverty.”

Davis said he knew there would be a lot of pain because retirees were on the verge of watching their life’s financial worth disappear for the most part.

“My own income dropped over a $1,000 a month. Even though I’m still young to receive Social Security benefits, there are many older retirees who have major medical bills. They are dealing with expensive prescriptions and have to come out of pocket for it now because they no longer have health care and cost-of-living adjustment,” Davis said.

At the time of the bankruptcy, his oldest son’s education at Michigan State University had to be put on hold because the tuition cost was depleting his savings.

“My son thought it was too much financial hardship on me because I was paying out of my pocket,” Davis said. “He dropped out and decided to go to Wayne County Community College. He then transferred to Wayne State University, where he will be graduating in December this year with his first degree.”

Evelyn Smith, who is in her 60s, was a longtime architect for the city who worked for the planning department before subsequently transferred to the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. She retired three years before the bankruptcy.

“About $800 is taken out of my retirement check each month. I was getting health care from the city but after bankruptcy I had to pay out of my pocket,” said Smith, who said she is now on Medicaid. “Nothing has been done for pensioners.”

After 31 years of service to the city, Smith said she didn’t regret working even though the city ended in bankruptcy.

“I served the city and I served well. I was proud of that. My only regret is how the city handled my business after I left,” Smith said. “They had no compassion for the people who have put in work for 30 years. I regret what has been done to us as retirees.”

For Richard Mack, a prominent labor and employment attorney who represented 3,500 union members during the bankruptcy, it was tough to witness the proceedings.

“The city carried an undeniably large debt load. But the decision to bankruptcy was rushed and decided behind the scenes without input from the people who had the most to lose,” Mack said. “For the speculating investors who took less-than-wise gambles, bankruptcy caused a slump in their otherwise diversified portfolios. But for a number of the employees and retirees, bankruptcy forced them to decide on buying food or medicine, being unable to afford both.”

He added, “Their losses should have been much less, if they were necessary at all. Their losses equated to employees reading this article being told: you thought you were working for $25/hour, but you are only going to receive $20/hour.”

bankole@bankolethompson.com

Twitter: @BankoleDetNews

Catch “Redline with Bankole Thompson,” which is broadcast at noon weekdays on Superstation 910AM.