Niyo: Red Wings legend Ted Lindsay lived, gave like he played — to the fullest

John Niyo

John Niyo

He was a throwback to a different era. But he was indispensable to the end.

Indefatigable, too, though that’s a word that made Ted Lindsay laugh when he saw it attached to his name in print once. He liked the sound of “tireless” a bit better, he once told me, though he knew they both meant the same thing.

“I’m not a genius,” Lindsay chuckled as he sat down for an extended interview about his life and his legacy just ahead of his 90th birthday back in 2015. “But I’m not stupid, either.”

No, even then at his age, he was still sharp as a hockey stick and looking for a fight, ready to take on all comers with his charitable work. And it’s that conversation that came roaring back to life upon hearing the news of Lindsay’s passing Monday morning at his home in suburban Detroit at the age of 93.

He was a hockey icon and a local hero, a Hall of Fame player without whom today’s NHL stars wouldn’t have half the millions they do. And as it was with so many of those Red Wings greats from his era, there aren’t enough hours in the day or drinks in the fridge to tell all the stories he could tell.

But with Lindsay, the conversations weren’t simply about story time. He liked to joke that he wanted his legacy to be “that I’m still living,” and that’s exactly what it was, and always will be, quite frankly. Life was one big lesson on living, the way he saw it, and few can say they learned from start to finish quite the way this man did.

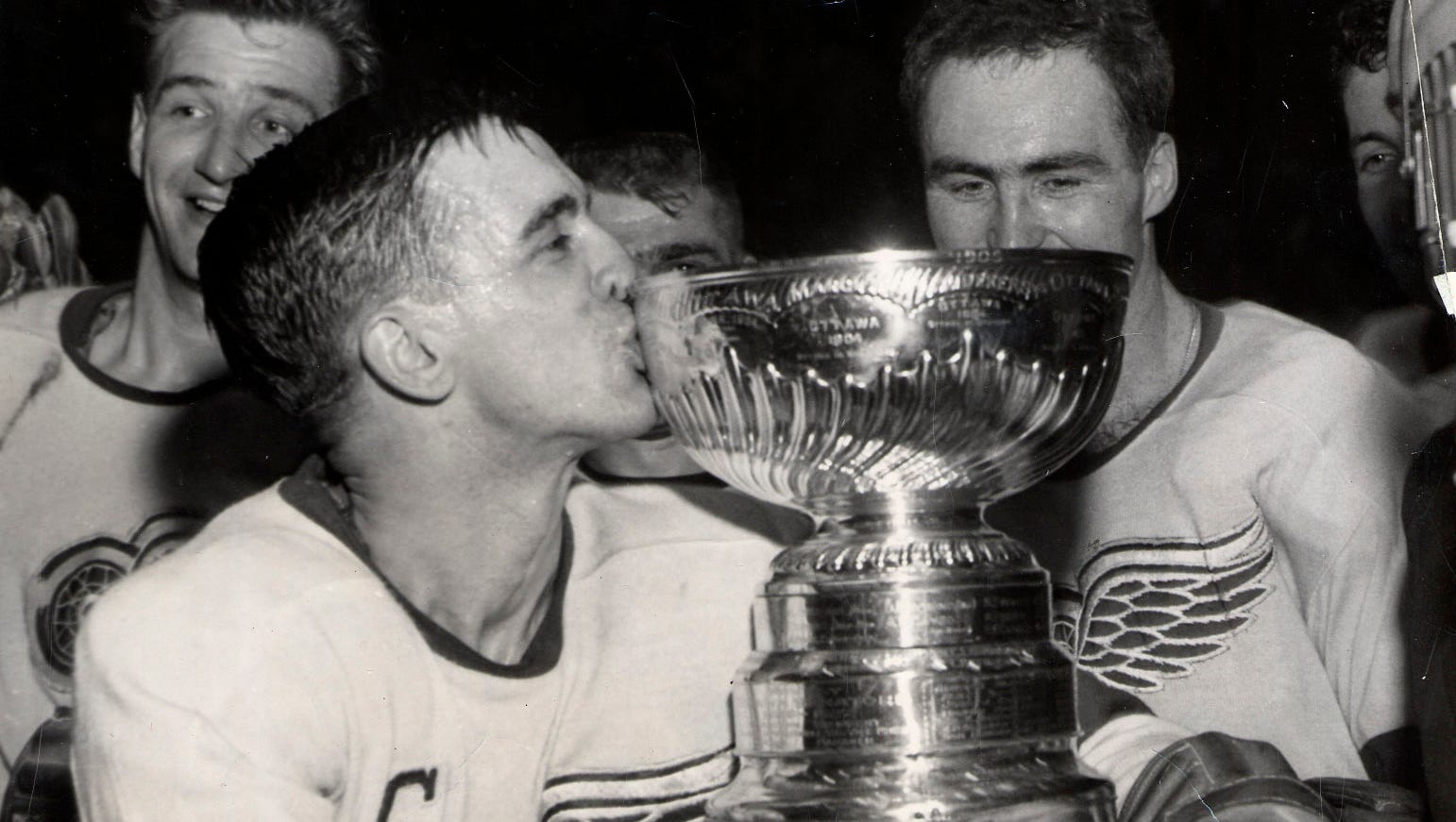

His credentials on the ice were impressive. An 11-time All-Star who once led the league in scoring, won four Stanley Cups as part of the famed “Production Line” with Gordie Howe and Sid Abel, and played in more than 1,000 games with the sort of ferocity that earned a 5-foot-8, 165-pound pit bull the “Terrible Ted” nickname we all adopted.

But his achievements away from the rink are what truly grew Lindsay’s stature.

At great cost to his own career and family, Lindsay led the organizing efforts for the first NHL players’ union in the mid-1950s. That fight got him exiled to Chicago — painted as a pariah by then-general manager Jack Adams — and ultimately led to an abrupt retirement a few years later. (He'd later return for one more triumphant season in Detroit in 1964-65.) But Lindsay's sacrifice laid the foundation for the NHL Players Association in 1967, and as Donald Fehr, the NHLPA's executive director, noted Monday, “All players — past, current and future — are in his debt.”

Promoting change

In 2010, the NHLPA renamed the Lester B. Pearson Award, given annually to the league's “most outstanding player” as voted by the players. It's now the Ted Lindsay Award, and the namesake was on hand to present it at the league's gala each spring until last year, when his health prevented him from making the trip to Las Vegas.

More:Krupa: Ted Lindsay's legacy leaves indelible mark on hockey

"A great honor," he called it. And that meant something coming from Lindsay, a principled man who actually boycotted his own Hockey Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1966, incensed that the event in Toronto excluded wives and families — “the most important people,” as he put it. A year later, the rules were changed, and Lindsay was an annual attendee every year after, his point made and his presence still requested.

Most fans don’t realize it, but his presence is still felt every June, when the Stanley Cup gets paraded around the rink. That’s a tradition Lindsay started on a whim after Detroit’s dramatic double-overtime win over the New York Rangers in Game 7 of the 1950 Finals at the old Olympia. Clarence Campbell, the league president, had presented the trophy to Adams, but rather than let it sit in ceremony on the table at center ice, Lindsay grabbed it and skated it over to the chicken wire with his teammates so everyone could revel in the moment, not just the players on the ice.

"I was just taking care of the fans who paid my salary,” he told me, matter-of-factly. “I wasn’t creating a tradition.”

He felt the same way during that brief tenure as Red Wings general manager in the late 1970s, preferring to watch the games with the paying customers as the franchise desperately tried to reconnect with its winning tradition.

“The people in the balcony were great hockey fans — they knew hockey,” Lindsay said. “So I used to walk the balcony. I never stayed down below. Those were the rich people. The hockey fans were upstairs. Those were the people who paid my salary.”

They were the same people who’d welcomed a small-town Canadian kid to Detroit a generation before, when a 19-year-old Lindsay signed his first pro contract, including a $2,000 signing bonus, in 1944 and later bunked with Howe and Marty Pavelich at Ma Shaw’s rooming house a couple of blocks from the Olympia.

He was born in Renfrew, Ottawa, but raised 300 miles north near the Quebec border in the small gold-mining town of Kirkland Lake, where his father sought work amid the Great Depression. He grew up listening to Red Wings games on the radio there — WJR’s signal reached Kirkland Lake on cold, clear nights — and Jimmy Orlando and “Black Jack” Stewart were his favorites, because “they played my kind of hockey,” Lindsay said.

More:Ted Lindsay's generosity reflected in battle to help those with autism

Lindsay didn’t learn to skate until he was 9, but by then, the youngest of Bert and Maud Lindsay’s nine children — six boys and three girls — knew how to scrap. And if you asked him where he got his competitive streak, he’ll start there.

“My brothers, they used to bounce me around pretty hard,” he said, laughing. “That’s where I learned to fight at a young age.”

And it was that fighting spirit that carried him all the way through, a refusal to back down from a challenge, even long after he’d retired.

This is a man, mind you, who opted to undergo elective heart surgery at the age of 88. (“Can you imagine?” Lindsay said, pulling down his shirt collar to show off his youngest scar.) And it wasn’t long after Dr. Marc Sakwa, the chief of cardiovascular surgery at Beaumont Hospital, replaced Lindsay’s aortic valve, that “Terrible Ted” was back to working out regularly dropping in with his duffel bag at the Training Room in Troy a few days a week to stretch and lift weights and work up a good sweat.

For a man who’d racked up more than 1,800 penalty minutes in his NHL career, and taken close to 700 stitches, by his own rough-hewn estimate, this was all part of the game.

More:Public viewing for Ted Lindsay will take place Friday at Little Caesars Arena

“One thing about reality is, we’re all gonna die sometime,” he said. “But I was blessed with a brain that recognized that the body is a muscle. And from the bottom of your feet to the top of your head, if you don’t work it out, it becomes flab. And flab becomes useless.”

'Always trying to do the right thing'

And Ted Lindsay was nothing if not useful. And it was during one of his visits to the Training Room nearly 20 years ago that he found his final calling. Upon learning that his physical therapist, John Czarnecki, had a young son, Dominic, who’d been diagnosed with autism, Lindsay asked one simple question: “What can we do for Dominic?”

Years later, the Ted Lindsay Foundation has raised more than $4 million for autism research and education, including a $1 million donation to expand the HOPE Center at Beaumont Children’s Hospital in Royal Oak and another $1 million pledge to Oakland University’s Center for Autism Outreach last fall. As Czarnecki said, “He’s always trying to do the right thing, no matter what.”

Mike Babcock was among many who revered the man. Though they became close acquaintances during his decade of coaching in Detroit, Babcock, now working behind the Maple Leafs bench, refused to address him by his first name. “He was Mr. Lindsay when I got here,” the coach insisted, “and when I leave here he will still be Mr. Lindsay.”

Everyone around the rink knew to give him that respect. And in Detroit, certainly, the players understood just how much he’d meant, not just to the Red Wings organization but to the game and the players’ place in it. The team always kept a stall with Lindsay’s nameplate in the dressing room, first at Joe Louis Arena and later at Little Caesars Arena, and Lindsay, a workout warrior to the end, made good use of it.

“It’s wonderful for me,” said Lindsay, who leaves behind three children from his first marriage (Blake, Lynn and Meredith), a stepdaughter (Leslie), six grandchildren and three great grandkids. “I never retired, really.”

He never really slowed down, either, until the last year or two, after the loss of his second wife, Joanne – “an absolute gem,” he called her -- following a battle with peritoneal cancer in February 2017. They’d been together for nearly 30 years, and not surprisingly, it was Joanne who'd managed to sum up Lindsay better than anyone.

“The way Ted sees it, if one is good, two is better,” she said. "He doesn’t know how to do anything half-assed.”

And bless him, he never learned.

john.niyo@detroitnews.com

Twitter: @JohnNiyo