Trammell and Morris: Hall of Famers left imprint on Tigers

They knew Hall of Fame baseball players typically draw upon two areas of exceptionalism.

Primarily, there is baseball skill.

Secondarily, there is the personal makeup that enables a player to maximize his talent.

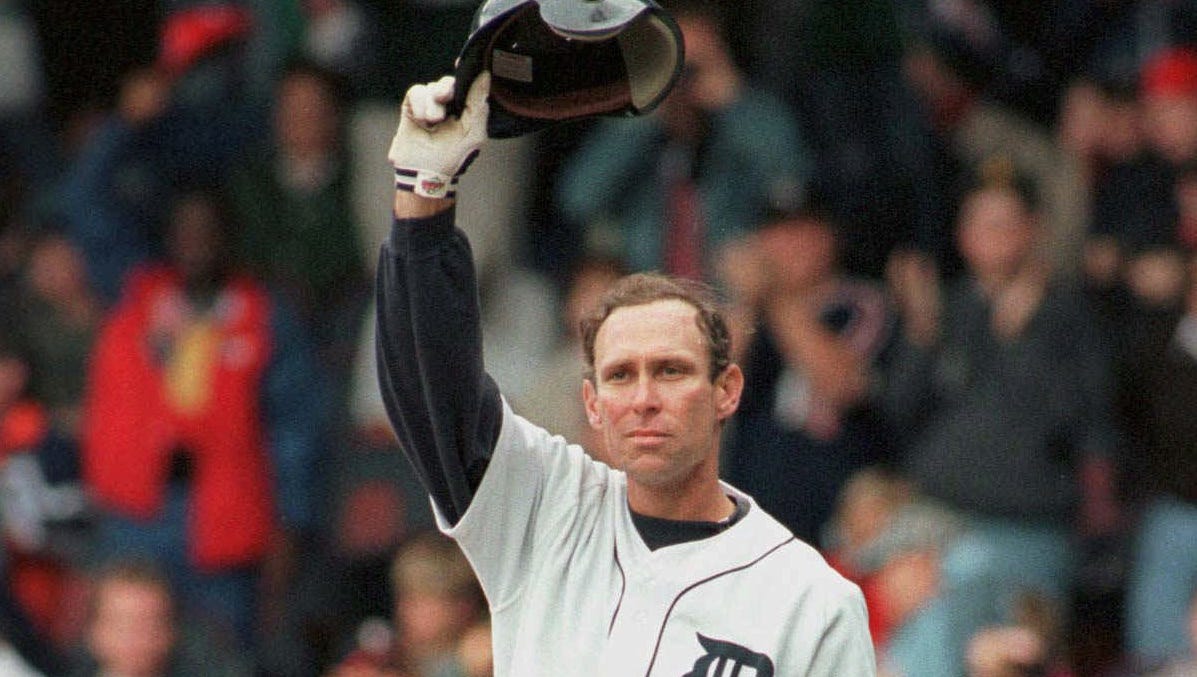

The combination, as unique to Alan Trammell and to Jack Morris as to any of the men who have gained a niche in the Baseball Hall of Fame, is etched in the minds of those who saw them play.

Those memories are best shared by teammates and those who were privileged to witness the lives and careers of two Tigers superstars who on Sunday will be enshrined at Cooperstown, New York.

Among sights, scenes, and moments from the two men's careers:

Aug. 16, 1980: Tiger Stadium

Morris starts a Saturday afternoon game against the Rangers, with an emphasis on “starts.”

He has a bumpy two innings, gets slapped for three runs, then is gone in the third. Rusty Staub, who a year earlier had been wearing Tigers garb, slams a leadoff home run ahead of a Pat Putnam single.

Sparky Anderson hails Bruce Robbins, who allows the runner to score, as well as four more runs.

Morris’ line: two innings, six hits, four runs, in a game the Tigers lose, 12-5.

The starting pitcher is not seen in the clubhouse afterward. Media interested in Morris’ insights will be left to their own observations and Sparky’s customary explanation that “everything was up.”

Ah, but of course it’s sometimes possible to talk post-game with a missing, angry pitcher or player as they head for the player’s parking lot at Tiger Stadium. The common path involves a stroll down the concourse and through a walkway leading to the lot.

Morris follows that very route.

He approaches, wearing a black cowboy hat, which was essential wardrobe in 1980.

There also appears to be figurative steam spilling from him as he stomps down the corridor, his eyes locked on a horizon only he could explain.

“Jack,” yells a young scribe as Morris marches on a boot-thumping line past him.

Morris never moves his head. Or his eyes. He is furious about the way he pitched. Furious that he was yanked two batters into the third. Furious that, today anyway, he was not Jack Morris.

Five days later he is back to being Jack.

He throws a one-hitter at Minnesota. The only Twins hit is a flared, opposite-field bloop single by Rob Wilfong.

You might get him once, he seemed to be saying that day at Minnesota after the previous Saturday’s fire had been quelled. But you won’t get him twice.

Dinner table at any restaurant in America

You didn’t want to be near Alan Trammell.

Every Trammell teammate will tell about his signature habit: Spilling food, or sauce, or ketchup, or smearing butter, or dumping his drink, or somehow turning his table place into a form of expressionist art.

“You’d fight not to sit next to him,” remembers Tom Brookens, who played alongside Morris and Trammell during their 1980s heydays and their minor-league years. “You wanted to sit across the table, or as far away as possible from the splash-zone.”

Brookens still laughs. All those dinners. All that mess. All that ribbing.

“He was going to knock something over on somebody,” Brookens said. “Then, to have had the great hands he did.

“We’d say, ha, great hands, my a--,” remembers Brookens, who played third base for the Tigers, and whose country-boy wit was another of the Tigers’ clubhouse hallmarks during the ‘80s.

Brookens turns serious, in an instant, about the ‘80s Tigers and the way they played baseball.

“It’s hard to put a Hall of Fame plaque on a player when you’re playing with them,” said Brookens, whose position had him in as close proximity as any player could be to Trammell and Morris.

“But we really wanted someone to make it from our group.”

Brookens hopes Lou Whitaker is next. And at any future dinner where his Tigers might celebrate Whitaker’s induction, Brookens says he will be sure to sit far from Trammell.

April 5, 1984: High in the Midwest skies

We were on the team flight from Minnesota to Chicago back when the Tigers flew commercial. They had just opened the season with a two-game pummeling of the Twins by a combined score of 15-4, and now the team was headed for Comiskey Park and for a weekend stand against the White Sox.

Other than the fact Sean Connery was somehow also on this flight, sitting in the front row of coach, this trip is remembered for something the famed Joe Falls said to his Detroit News partners as we awed at Connery, who was parked across the aisle a few seats to the right:

“There’s going to be a great baseball game this weekend,” Falls said in a matter-of-fact voice.

One night later, after the Tigers had won Friday’s series opener, 3-2, there was a customary, post-dinner trip to one of Rush Street’s saloons, a place then called the Hange-Uppe.

Among that night’s patrons was Jack Morris, having a splash with a teammate or two.

He was only 12 hours from an exercise in baseball history.

The next afternoon, chilly and gray, he sliced up the White Sox with such early precision that we called the office in the fifth inning.

Prepare for a no-hitter, bosses were told.

Morris got it – the first Tigers no-hitter since Jim Bunning had done it to the Red Sox in 1957.

After the game, Ron Kittle, the tall White Sox slugger, was asked by the Chicago Tribune if there had been any appreciation for being involved in Morris’ slice of baseball eternity.

“All in all,” Kittle said, “I’d have preferred that he bowl a 300 game.”

Spring training 1985, Lakeland, Fla.

The Tigers clubhouse culture has returned for another year, complete with its frat-house ways.

That means a trick or two is up someone’s sleeve, usually Trammell’s.

The position players have been ribbing the pitchers, Morris principally, about their Florida “regimens.”

Ah, the position players say, you guys have it made. Pitch every five days. Do a little superficial maintenance on the other mornings. Ah, must be nice.

Morris, of course, is an outdoorsman and always makes the most of his Florida time. Bass, wild boars – he’s always fishing or hunting for some species.

Morris arrives in the clubhouse to see a big rectangular piece of paper stuck to the bulletin board with his name on it. It says:

JACK MORRIS SCHEDULE

DAY ONE

Show up.

Pitch in game.

Go home, relax.

DAY TWO

Show up.

Do stretches.

Go bass-fishing.

DAY THREE

Show up.

Do short run.

Go hog-hunting.

DAY FOUR

Show up.

Light bullpen.

Go gator-snaring.

Morris, of course, snorts fire when he sees it – his teammates’ giggles drown it out – all while he unleashes his mix of mock-rage and retorts.

Privately, anyway, he’s as amused by the prank as Trammell and Brookens and Gibson, the likely perpetrators.

These Tigers baseball boys never suffered from a shortage of fun.

1980-83, MLB ballparks

Oh, it could be a double-edged sword catching Morris.

All that talent. All that fury. And all that stubbornness.

Lance Parrish occasionally would get fed up.

It would be at some point in a game, typically in the early or mid-innings, and Parrish, the everyday Tigers catcher, was about done trying to unite a game plan with Morris’ ire and demeanor.

Sparky Anderson would step from the dugout, headed for the mound and a chat with his ace. Recognizing that Morris was either agitated or on his own path to self-combustion, the skipper would be ready to counsel, or command, or urge, or loosely suggest that Morris might want to finish this inning rather than get the equivalent of a child’s timeout.

Parrish – when he had reached his personal ceiling – sometimes would do something catchers simply didn’t do when the manager came to the mound.

He stood behind home plate – his way of saying to the skipper, “You deal with him.”

Parrish laughed when asked about those occasional mound boycotts.

“I remember doing that a few times,” said Parrish, who now manages the Tigers’ Single A club at West Michigan.

Anderson, who was by-the-book on protocol, understood.

“He never said a word to me about that,” Parrish said, turning to why he and Morris might have been having a tiff. “I don’t know if it was shaking me off too much, or that I was just up to my eyebrows with him, or whatever was happening during the course of the game, or how he was acting.

“But it never went beyond that,” Parrish said. “I had to find ways to make my point and show my disdain for what was going on between the two of us. I figured that was as good a way as any to make my case.”

More often, they found themselves in a groove. All because the pitcher was so talented he could engineer his own groove.

Notice that last strike of Morris’ no-hitter in 1984.

The guy sprinting toward him, wrapping him in a bear hug, is the man who caught every pitch.

Lance Parrish.

1982-88, MLB ballparks

Larry Herndon saw it all happen from left field, his position in Detroit during the best of the Trammell-Morris years.

He saw in Trammell a guy who always looked a bit like a kid, at 6-feet, 165 pounds, but who played – and knew the game – in the fashion of a seasoned man.

“There was just this intelligent perfection to his game,” said Herndon, who now lives in Memphis, Tenn., and who on Thursday was at his 13-year-old grandson’s basketball clinic. “If he’d throw across the diamond, every one of his throws would be right at the (first baseman’s) chest. But that’s how he prepared – every single day.

“And then you talk about Jack, who never wanted to come out of a game until it was finished.

“The thought that comes to mind most often about them is: humble warriors. They didn’t ask for nothing special from anyone else. They didn't expect any favors. They were honorable and kind men who took care of everyone in that clubhouse," he said. "They were unselfish, always picking up everyone, making you feel good – that whole group: Lance Parrish, Kirk Gibson, Tom Brookens, Dan Petry, Darrell Evans – everyone.

“It was such a beautiful clubhouse. And now we get to watch Tram and Jack get the Hall of Fame.”

Herndon’s hope: That eventually Whitaker, too, will have his Sunday at Cooperstown.

Summer 1984, Tigers clubhouse

Johnny Grubb had been brought aboard a year earlier as a perfect tribute to then-general manager Bill Lajoie’s sense for roles and craftsmen. Grubb was your classic “professional hitter.”

He also was loved by his teammates. There was joy, and peace, and always a smile when Grubb was anywhere but at home plate, where his beautiful left-handed swing so often defeated a pitcher.

He also was a hoot, this Virginian who wouldn’t say a profane word if he were held naked over an open fire.

Grubb was awarded a nickname by his teammates: Johnny Chaptail. It stemmed from a day in the clubhouse in ’84 when the guys were telling stories and Grubb recounted a time in the minors when an umpire rang him up on a called third strike with a “take a hike” dismissal.

“That really chapped my tail,” Grubb said.

The guys howled. And there begot the title “Johnny Chaptail” whose biggest hit during six seasons with the Tigers was a 11th-inning double against the fence that beat the Royals in Game Two of the 1984 ALCS.

When it’s mentioned to Grubb that Trammell seemed so much stronger than a player his size figured to be, Grubb agrees. Trammell hit 185 home runs, 28 of them during a 1987 season when in the minds of many he should have been the American League Most Valuable Player.

“He would probably surprise you there,” said Grubb, who still lives in his native Virginia and who next week turns 70. “He was always working that (exercise) machine, strengthening his hands. He’d surprise you, strength-wise.

“It’s not always how big you are, but how you work your baseball muscles. Alan was stronger than most people think. And the other thing is Alan had a very strong mind. You weren’t going to beat him mentally.”

That, Grubb adds, was also true of the team’s ace, Morris. Grubb saw that Morris’ insistence on winning, on being as close to perfect as was possible, could lead the team’s ace “to take things a little too hard, beating himself up.”

But he loved how Morris grew there and, with Trammell, embodied a champion team’s kinship.

“I enjoyed my time with both of them. They actually have helped me become a better grand dad,” said Grubb, who isn’t able to be at Cooperstown this weekend.

“But I’ve already sent them congratulatory cards. I’ll be thinking of them. And watching the coverage. I think we players, and the fans, felt that one of these years, this was meant to happen.”

lynn.henning@detroitnews.com

Twitter @Lynn_Henning

HOW TO WATCH

What: Tigers greats Alan Trammell and Jack Morris will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

When: The induction ceremony is Sunday at 1:30 p.m.

Where: Cooperstown, N.Y.

TV: MLB Network

Notable: Four other players will be inducted: Vladimir Guerrero, Trevor Hoffman, Chipper Jones and Jim Thome.