Krupa: Ted Lindsay's legacy leaves indelible mark on hockey

Gregg Krupa

Gregg KrupaDetroit — Ted Lindsay, an integral player in some of the Red Wings’ greatest triumphs and a revolutionary figure during his seasons in the NHL, came up in a different era.

And, in his childhood, Lindsay was a fan of the Wings.

“When I grew up in Kirkland Lake, Ontario, I never played indoors,” Lindsay said of what he constantly called “the greatest game” ice hockey.

“Every school had two natural ice rinks. We were never indoors. Our temperature was often 15-below.

“The Red Wings used to be broadcast on WJR. On a clear, cold night, we could get WJR in Kirkland Lake like you were in downtown Detroit. And, they had two tough defensemen, Jimmy Orlando and Jack Stewart.

“Good, tough,” he said.

“That was my kind of hockey.”

Good, tough.

That was Ted Lindsay’s kind of life, too.

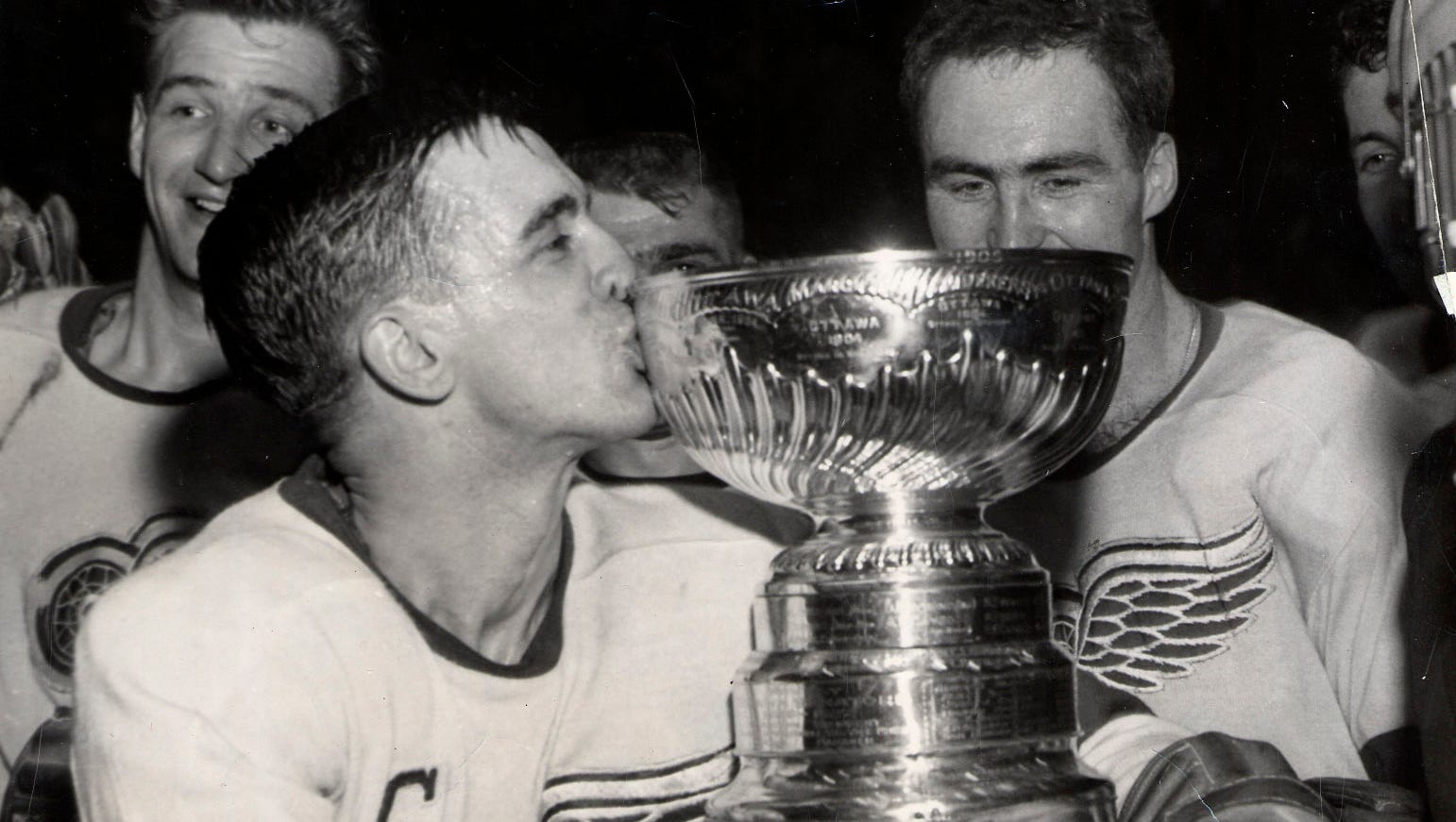

In winning four Stanley Cups with the Red Wings from 1950 to 1955, he set a standard for tenacity rarely paralleled in the tenacious sport. “Terrible Ted” could be punishing and painful.

But, on The Production Line, with Gordie Howe and either Sid Abel or Alex Delvecchio, Lindsay sometimes scored at will.

His 78 points in 69 games played in 1949-50 won the Art Ross Trophy for the top scorer.

During his 13 seasons with the Red Wings, before he was run out of town in 1957 for his nearly successful rebellion trying to organize a players’ association, he was a First-Team All-Star eight times. He came out of retirement to play one season for the Wings in 1964-65 where he scored 14 goals and had 28 points in 69 games.

“I’m lucky,” Lindsay said. “I played the greatest game in the world.”

Point producer

In 862 regular season games played for the Wings, Lindsay produced 728 points, 335 goals and 393 assists.

While engaging in labor activity in his last season in Detroit, 1956-57, he scored 30 goals, led the league with 55 assists and achieved a new career high for points with 85.

Despite standing at 5-foot-8 and weighing only 168 pounds, he famously and infamously yielded not an inch. Like Howe, Lindsay said he played pugnaciously to create space and time on the ice for him and his teammates.

“We all played with every ounce we could muster,” he said in a 2014 interview of the great Red Wings teams of the 1950s. “We were side-by-side in battle, every night.

“I got the idea early on that I should beat up any player I tangled with, and it never occurred to me it was a bad idea.”

Friendship forged

Lindsay arrived in Detroit at age 19, two seasons before Howe, arrived at the same age.

“My closest friend at that time was Ted Lindsay, a tough kid from northern Ontario,” Howe wrote in his autobiography, “Mr. Hockey.”

“He came from a rugged mining town, which probably had a lot to do with his temperament. Hockey fans from that time know that Ted played the game like a holy terror.”

Coach Jack Adams put the two young friends on either side of the veteran center Sid Abel in 1947-48.

The trio often stayed late after practice, perfecting the “set play.”

Either young winger would angle a shoot-in just after cross center ice so that rebounded off the boards towards the goal. The other winger retrieved it and either fed Abel or shot.

In an era in which goalies almost never left the crease, the hybrid version of “shoot and chase” worked constantly.

The line led the team in scoring that season.

Powered by the awesome trio, the Red Wings started beating the Maple Leafs and Canadiens in the playoffs and, with Alex Delvecchio eventually replacing Abel, they won four Stanley Cups in five years.

“You know,” Lindsay said. “At one time, we were the greatest line in the history of the game.”

Howe called it “a match made in heaven,” and recalled the intense camaraderie.

“It began with stars like Sid Abel and Ted Lindsay and carried all the way down the roster,” he said. “You never wanted to look down the bench at your buddy and know that you let him down.”

There were others, generations of players, Lindsay refused to let down.

He earned $6,500 to $7,500, good money for the early 1950s. But, younger players made half and had to pay their own expenses when bouncing between leagues.

“I just saw what was happening,” Lindsay said. “I thought it wasn’t fair.

“It was dictatorship, at that time.

“I was one of the best hockey players in the world. I’m not bragging. It’s just a fact. And, I thought that there was something I should do. Because those kids couldn’t argue with management.

“So, I did what I believed in.

“And, I’d do the same thing all over again. Because it was wrong, the way they were doing the darn thing.”

The first attempt in 1957 failed, with Lindsay traded to the then-lowly Black Hawks.

The union would not form for another 10 years.

The NHL Players Association honors its “founder,” by naming its annual award for the most outstanding player in the regular season the Ted Lindsay Award.

Asked about the good that often complemented the tough in his life, Lindsay described it as simply a matter of course.

“Well, I guess, I had wonderful parents,” he said. “I was given values: To be honest. Not to cheat.

“That’s a dying thing in this world, today, unfortunately.”

The funeral service for Ted Lindsay will take place at 10 a.m. Saturday at St. Andrew Catholic Church, 1400 Inglewood Avenue in Rochester. It is not open to the public.

A public viewing will take place for Detroit Red Wings great Ted Lindsay from 9:07 a.m.-7:07 p.m. Friday at Little Caesars Arena. Lindsay died early Monday. He was 93.

krupa@detroitnews.com

Twitter: @greggkrupagregg