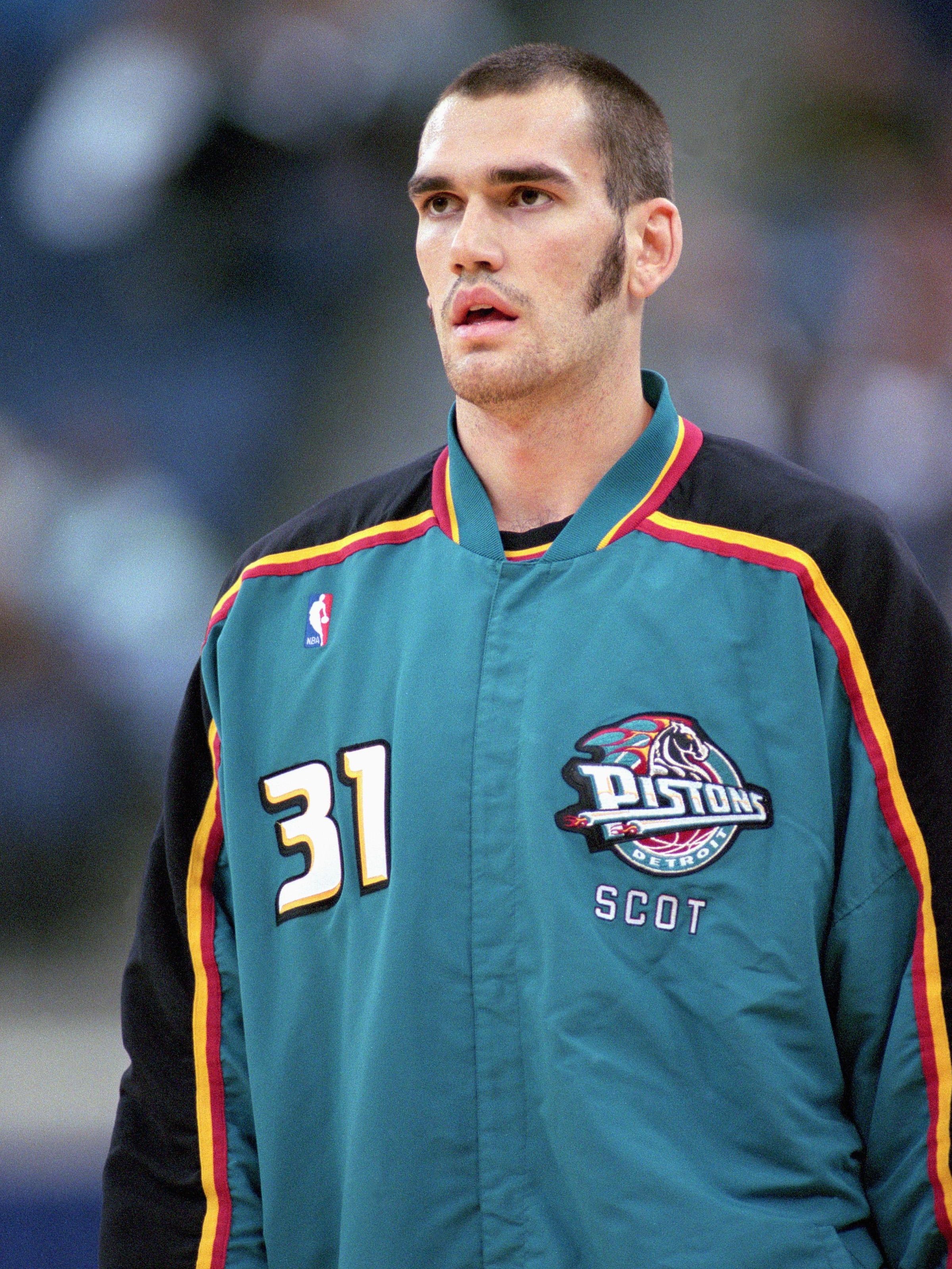

After heart transplant, ex-Piston Pollard plans to campaign for organ donations

Former Piston Scot Pollard had grown so accustomed to his weak and failing heart that he didn’t realize how close he was to dying.

“Oh, boy. That thing was a wreck,” Pollard told The Associated Press on Friday, a day after he was released from the hospital and two weeks after he received a heart transplant.

“The doctors immediately knew I was much closer to death once they pulled my heart out,” Pollard said. “I don’t think I would have made it another couple of weeks.”

An 11-year NBA veteran who was a member of the 2008 champion Boston Celtics and averaged 2.7 points in 33 games for the Pistons in his rookie season in 1997-98, Pollard inherited a condition from his father, who died at 54, when Scot was 16.

Scot Pollard's heart deteriorated quickly after he contracted a virus in 2021; attempts to fix the problem with medication or less radical procedures were unsuccessful, leaving a transplant as the only option.

But finding a heart big enough to pump blood throughout the body of the 6-foot-11, 260-pound former NBA center was a challenge. Pollard was advised to list himself at as many transplant centers as possible (though they needed to be nearby, so he could be available within four hours if a donor heart became available.)

Pollard, 49, underwent pre-transplant testing near his home in Carmel, Indiana, and Chicago, but when he arrived at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center last month he was admitted to intensive care and bumped up to the second-highest priority for organ transplants, because of his condition.

Nine days later, his wife, Dawn, posted on X: “ It’s go time!”

“The fact that it came so quick probably saved my life. I don’t know how much longer I would have lasted,” Scot Pollard said. “I was just declining so fast.”

Privacy rules don’t allow Pollard to know the identity of his donor, though doctors told him it was “a big man.” What is allowed: A recipient can write a letter that will be delivered to the donor’s family if they want. (They can also write the recipient, though Pollard had not received such a letter yet.)

Speaking from temporary housing in Nashville, Tennessee, where he needs to stay for the next six to eight weeks so he can have the proper follow-up care, Pollard said he has written a draft of his letter. In it, he thanks the donor – whom he calls a hero – and offers to connect.

“I would like to show them how their big man’s heart is living on and helping people,” he said. “I would love to show them this heart isn’t going to waste.”

Pollard has been warned that many donors’ families don’t want contact with the recipient, because it makes them relive their loved ones’ death. Heart donors, in particular, are often accident victims who were otherwise healthy.

“If it’s a healthy heart, that’s because something else killed them,” Pollard said. “I hope they reach out, because I would like to include them in the rest of my life.”

That life has already improved.

Even after he retired from the NBA, Pollard liked to keep busy – with broadcasting, a few acting roles and as a reality show contestant. But over the last few months, he needed to stop to rest even just walking around the house.

It was only when he woke up after the five-hour surgery that he realized how bad things had gotten.

“I was laying around all the time. That just became my new normal,” he said. “As an athlete, you just sort of put things out of your mind. You push through it. But I couldn’t push that heart. I can already tell I can push this heart.”

After the transplant, which was performed by Dr. Ashish Shah, Pollard was walking around the hospital ward within a day. He is now up to “easy squats,” and working on his balance.

“I’m a mover. I don’t sit around well,” Pollard said.

On Thursday, Pollard danced and shadow-boxed his way down the hospital corridor in a tank top that said “BUT DID YOU DIE?” His care-givers applauded as he yelled “I’m getting out!” and mugged for a camera as he rang the discharge bell.

Pollard said he is going to campaign for organ donation.

“I’m going to annoy people with becoming a donor. That’s going to be a project for the rest of my life,” he said.

He's already helped convince one person to sign up.

“I had never considered being an organ donor, because I wasn't really educated about it and there were some fears when I thought about the process,” Dawn Pollard said. “It became our reality that Scot needed a heart, so I immediately got registered. I am proud to be an organ donor now. It makes me feel good knowing I could be helping someone live.”